CHAPTER I. A DREAM.

It would be impossible to find in the wide world a more thorough disbeliever in ghosts than I was in the year 18—. An Eton boy, full of life and spirits, fearless and active, I was the last person to believe in anything approaching to humbug. That is what I should have said in those days, and I say it now to show you how ungenial was the soil which was yet destined to produce a goodly crop of faith. In that said year, 18—, Harry Bandeswyke and I, aged respectively eighteen and seventeen, matriculated together at —— College, Oxford. We were great friends and constant companions, Harry and I, and were as different in every way as great friends generally are. He was a big fellow, six feet six without his shoes, brave, sweet-tempered, silent, lazy. A man to sleep soundly through a Walpurgis Night, to yawn and go to sleep again if he chanced to wake while the spirits raged around him. I was slight and excitable, with a quick temper, and no lack of words. Yet we were sworn allies.

He was heir to a goodly property in Wales, which, however, he had never seen. It belonged to distant cousins, and, besides a fine old castle and many acres of mountain, there was a fine old quarrel to keep up. With a lamentable want of respect for the originators of the feud, the present possessor of that great privilege appeared inclined to stretch forth the hand of friendship to his heir. In point of fact, he did stretch out that hand at the time my story begins, and invited Harry to spend the vacation at the Dumberdene, for this was the extraordinary name of an extraordinary place. Harry was engaged to me; but his answer to that effect producing a cordial invitation to bring his friend with him, we at once resolved to go.

It was a long journey in those days, and we arrived late after a tedious drive, for the Dumberdene was in the wildest part of ——, far in among the mountains. The evening gloom was deepening as we turned into the park, and even then we had another three quarters of an hour's work before us; for, after a short run on level ground, we began to ascend another interminable mountain zigzag. At length, after a short pull more abrupt than any we had yet experienced, the carriage came to a stop, and I exclaimed with regret that it was too dark to see the house. We were mistaken. It was only too dark because we were already in the house. The carriage rolled forward once more through a short passage cut out of the rock, and we found ourselves in a hall of vast dimensions, lighted by a huge lamp in the centre, and a bonfire of wood at each end. That was our first entrance into the Dumberdene. We both burst out laughing with boyish glee. Ah, could we have foreseen how sadly linked with our future lives was much that was very near us then, but of which we little dreamed!

We were most kindly received by Mr. and Mrs. Bandeswyke, and their only child Gwen. I suppose the name of the latter was Gwendolin, but I never heard her called anything but Gwen. She was tall, fair, and stately. A face calm and self-possessed; grand with the beauty of a pure and truthful spirit portrayed in each feature: a woman to trust in the hour of danger. Her father was, with the exception of Harry, the most silent man I ever met; perpetually brooding over—what? A crime? a mystery? a problem? The mother was commonplace enough; small, dark, active, and energetic; managing everything and everybody, and talking enough for husband, child, and cousin. We were alone. Mrs. Bandeswyke told us with many apologies that the friends who were asked to meet us could not arrive till the following day. She feared we should find it dull. I feared so too, and vehemently asserted the contrary. Gwen was evidently not the young lady to amuse my passing hour. Harry's silence always appeared sufficient unto him. The family retired to rest early, leaving us alone. Mr. Bandeswyke apologised in fewer words than I should have thought possible. He was somewhat of an invalid. He hoped we should make ourselves quite at home.

"Lively work," said I, as the door closed; "I mean to go mad, Harry; will you?"

"Certainly."

"It is a queer old place. Fancy rumbling into the ancestral hall in one's carriage. I don't half like it. It is producing a bad effect on my delicate constitution. I feel ghostly all over. I am already suffering from ghost of the heart, ghost in all my limbs, very bad ghost indeed in my head and face, and shall shortly die of delirium ghostums. Harry!"

"Well?"

"How do you feel in the abode of your ancestors?"

No answer. To this I was accustomed, and I rattled on as usual; walking restlessly about the room, peering behind the tall old-fashioned screens, and looking into the quaint cabinets.

Presently I proposed that we should explore the rooms near us.

"No," said Harry, in a voice which meant no. He would have done it in any other house, but this was to be his own some day. Then I suggested that we should go out and smoke. It was our last new accomplishment, for those were days when boys did not smoke until they were called young men, and girls did not flirt till they were seventeen. We have changed all that now, and the poor young people are no longer deprived of these privileges for four or five years.

Harry rose, and stalked to the door. We had some difficulty in finding our way out. In fact, we wandered to the butler's room, and had to be set right and to encounter sundry remonstrances from that individual, an old and privileged servant. It was pitch dark when we stood outside the house, but presently the moon passed from behind a cloud, and we stepped forward to have a look at the place. It was an enormous pile of building, very ancient, especially one portion, which, partially in a ruinous state, stretched away so far among trees, foliage, and mountains, that in the pale moonlight we could not discern where it ended. We both uttered an exclamation of astonishment, and I turned to Harry with a low bow, and congratulated him on his heirship to this mass of ghostliness and ruin.

"Don't be an ass," said Harry, as he moved towards the house, for at this moment the moon was again obscured, and a driving rain set in. We had gone out by a side door, and though we returned by the same, we again lost our way, and found ourselves, after much wandering, once more in the great entrance hall. I knew that our rooms were not far off, and professing an accurate knowledge, I went on first with the light. Harry lingered, and I looked back to see why he did not follow me. He was standing at the entrance of the passage down which I had turned, and was groping about with his right hand, as if struck with sudden blindness.

"What is the matter?" said I. "Come on, can't you?"

"I can't find the handle of the door," said he, still fumbling.

"What door?"

"The door you shut."

"I shut no door. There is no door," said I, laughing; but it just passed through my mind, though I did not remember it till afterwards, that his voice did sound muffled, as if a door were shut between us. I stepped back into the hall. There was no door; and as we walked back together, I laughed at Harry, and asked him if he did not think he too was suffering from delirium ghostums, or at least a slight attack of ghost in the joints.

It was the wrong passage after all, for it ended in a real door of immense thickness, bolted and barred. Soon after that we found our way and our rooms, and went to bed.

I had a dream. Such a dream. I was wandering about the house again with Harry. Endless passages, dark, gloomy, and damp, crowded with pictures and quaint old furniture; long low rooms, dimly lighted by deep slits of windows, over which the ivy hung in thick festoons. Presently I stumbled, and fell rather heavily against a projecting fireplace, one side of which started back with a creak, leaving an aperture large enough to admit a man. Through this we crept into a room. It was small and many cornered, crowded with rubbish and pervaded by a faint sickly odour. Blackbeetles and other huge insects raced across the floor as we advanced. The ceiling was covered with flat globular insects, nearly an inch in size, and sending forth a dreary creaking sound. "What can these be?" said I; and something seemed to answer, "These are cocoons." These creatures have nothing to do with my tale. I did not at the time know the meaning of the word, and I merely mention the circumstance as part of my dream, proving that it was a bonâ-fide one, characterised as dreams usually are by all that is odd and unconnected.

A mass of something which looked like a woman's dress lay in the window, but covered with the dust of centuries and undistinguishable in the dim light, for the room was low and dark, and the shutters half-closed. As our eyes became accustomed to the gloom, we perceived in one corner a tattered bed; it was very small, but its appearance was indescribably dreary, and we felt such horror that for some moments we recoiled from approaching it. The heavy tapestry curtains were closed all around. Every fold hung straight down, and seemed to breathe mystery. At length we advanced together, and with trembling hands drew them back. On the bed lay the figure of a child in the dress of a century past, the head half buried beneath one arm, the face turned to the wall. A luxuriant growth of long sad-coloured hair half concealed the body.

Harry and I gazed in wondering incredulity. We dared not touch the cold still form. We dared not look on the young dead face. As we gazed, a faint air stirred the heavy atmosphere, and we distinctly heard a whisper pass by us: "So has he lain for a hundred years." My heart was thumping against my side—drops stood on my forehead. I would have fled. Harry stopped me. His face was deadly white, his mouth firmly set as he leant over the body and gently turned the face to view. It was that of a beautiful child—a boy. Beautiful still, with a singular expression of sweetness and patience, in spite of the terrible emaciation, and of a quaint look of old age, which I have since learnt is produced by suffering and starvation. There were no signs of decay, but the flesh, for flesh it was though shrivelled, was of one uniform light-brown colour. As we still gazed with painful fascination, the head still resting on Harry's arm, a long tremulous shiver ran through the whole frame, the eyelids slightly quivered, the limbs attempted a faint stretch, and then falling from Harry's almost paralysed hands, the whole form fell back as before. We fled in uncontrollable horror. Here my dream became indistinct, and I can recall but two other incidents. We were still wandering about the house, with a feeling of awe and an ardent desire to find our way out, when, pausing for a moment in a dark passage, we both distinctly heard a deep sigh close to us; and as we grasped one another's hands in horror, footsteps approached us—uneven, halting footsteps, with a squeaking sound of iron against iron, as though one walked with an iron frame. Soon after this, we were in a gloomy gallery, in which the pictures hung strangely, not against the wall, but from the ceiling. They were moved slowly and grimly backwards and forwards by the draughts of the old building. One moved, not backwards and forwards, but up and down. It was the picture of a large fair woman, with a hateful face; a cruel wicked face. There was a slight squint in the eyes, and the heavy flaxen hair was brought very forward over the brow, and bunched out on each side. She was dressed in crimson velvet, over which hung long black robes, which swept the ground. In her hand was a lighted candle, which cast a lurid red light on her bare arm and on one half of her face. In my dream I stopped before her, and with a ghastly effort to overcome the scene of terror, boldly asked her:

"Why do you move like that?"

There was a long shivering whisper, every word as distinct as possible.

"Because I loved dancing too much in my past, and now they will not let me rest."

They were mocking tones, and instinctively I knew that it was a lying whisper, and in my heart I hated that woman. Yet I could not leave her, and tauntingly I remarked on the quaintness of her long black robes, and said I should like to have them for a masquerade. I was no way surprised to see her slide down from the ceiling and step out of her frame; but I felt half strangled when, after taking off the black robes, she passed her dead arm round my neck to fasten them upon me. Beautifully formed and white as snow, half that arm was of icy coldness—half burnt like fire. After that all was confusion. Only I know that Harry was no longer with me. I was alone, yet not alone, for every picture was astir. Men, women, and children stepped out of their frames, some turning and hanging them carefully up, others smashing every atom. They walked up and down, wringing their hands and moaning bitterly. The backgrounds were a sore puzzle to me; some remained in the frames, but some still clung to the figures. That was the only thing that surprised me. If a picture disputed the passage with me, I merely replaced him in his frame. If he did it again, I hung him up. Some stood back to let me pass, others turned to follow me. One old man caught his wig in his own frame, and I was in the act of helping him, when I turned into a picture myself, and was hung to the ceiling by the cruel-faced woman.

At this moment I awoke, to find myself in bed, a person and not a picture, but a more uncomfortable person than I ever remember to have been before. Drops of moisture stood on my face, my very hair was wet, my heart beat painfully, and when I tried to get up, I found myself too giddy to stand. It was the very strongest possible proof of the impression that dream had made that I did not at once call out for Harry. I staggered to the table and took a long draught of water, and then staggered back to bed to recover as I could.

CHAPTER II. AN ADVENTURE.

I managed to be in time for breakfast, and to keep out of the way of Harry's remarks until I had somewhat recovered myself; but not one word of my dream did I breathe to him or anybody else. The day was long and dull, to me at least, although it was chietly spent in walking and riding over the property at some future time to be Harry's.

He was not dull, for Gwen was with us all day; and although it was hardly a case of love at first sight, that good calm face had evidently a growing attraction for him. Mrs. Bandeswyke meant that it should be so, and was officious enough to have spoiled all. Harry, however, seemed scarely aware of her existence in the fascination of her daughter's presence, and to the same cause I attributed his taking no notice of my unusual silence.

After breakfast we all set forth to look over the house, first going out of doors to gain an idea of the exterior. I had never even imagined such a place. Its size alone made it remarkable, and the massive walls and buttresses, the enormous beams, and narrow loop holes of windows suggested the idea that it had been originally built for defence. It stood on a terrace or table-land of the mountain, which towered thousands of feet above it at the back, and descended precipitately about a hundred yards from the front. Yet few places could be more entirely concealed from view from below, for gigantic arms of rock formed a natural wall of great height on the edge of the precipice, entirely enclosing the castle, which was only approachable from two points. A short artificial tunnel hewn in the rocks at the back, and guarded by a portcullis, admitted the carriage road into the very house, while a natural gap in the rocks in front let in a narrow view of the glorious landscape below, and formed the entrance to a short flight of steps leading directly to a mountain path which rivalled the Wengern Alp for abruptness and beanty. So completely was the castle, in the oldest part, built into the rock, that God's work and man's work were here hardly to be distinguished apart. The difficulty was increased by the partially-ruined state of this portion of the building, and still more so by one peculiar feature of this magnificent place, viz. the luxuriance of the trees and foliage. Three enormous cedars partially concealed the ruin from almost every point of view, and the mass of foliage which crept down the mountain side entwined itself alike round rock and stone, brick and buttress. The morning light showed us that the hall into which we had driven the night before divided the older building from the more modern part, which alone was inhabited, and I made the farther discovery that our bedrooms were the last occupied rooms on that side, and were consequently adjoining the deserted portion of the castle.

When we had looked and admired long enough, we passed through the great hall to the cloisters, and from thence to a gloomy chapel full of banners and escutcheons of many a generation past. At the end of all the sight-seeing, we found ourselves on the battlements, from which a fabulous number of counties and churches were to be seen. We returned to the house by a trap-door and short steps into a low dark lobby, full of rubbish, boxes piled up, old furniture, injured pictures, &c.

"The lumber-room," said Mr. Bandeswyke shortly, as he led the way rapidly to the staircase. My attention was attracted by a curious old screen, and I stopped to examine it. Behind it was a door so curious that I called to Harry to come and look at it. It was arched in form, and of immense strength, though very low. Five bands of iron nearly a foot in breadth were nailed across it.

"Surely, sir, this is a curiosity," said I, turning to Mr. Bandeswyke. He was gone, but Gwen stood beside us. Gwen and Harry and I. Ah, once more were we destined to stand side by side at that door!

"It is," said she, answering my remark; "it leads to the old part of the house, which my father considers unsafe, so that it is never entered. I believe this door has sad associations for him. He never likes to hear it talked of."

At another time I should have teased Gwen with boyish curiosity to tell us more, but the oppression which I could not shake off kept me silent. By five o'clock the day set in for rain. By six, we had one of the most tremendous storms it has ever been my lot to witness. Our ride had been cut short, and we were employing our selves as best we might in the billiard-room, when the door burst open, and the old butler tottered into the room. There was that in his appearance which made us leave our game and gaze at him with astonishment. His head trembled, his dress and hair were disarranged and wet. Evidently he had been out in the storm.

"Master, the tree's down, and this is the 26th August!" he exclaimed in a choked voice. And Mr. Bandeswyke, the last to see him, turned suddenly in the very act of playing, and promptly responded, "You old fool!" in a tone of such energy, and a manner so different from his usual reserve, that Harry and I looked at one another in amazement.

Mr. Bandeswyke and his servant vanished behind the swing-door almost as soon as the two sentences were uttered, and Gwen recalled us to our game with a composure which made us feel that the incident was no business of ours. Mrs. Bandeswyke had less tact, and poured forth excuses for master and man. Gwen quietly stopped her with the remark that Ransley was a very old servant, and so attached to the place that the loss of a single tree was a real trial to him. With a mind prepared to receive strange impressions in this strange place, I however fancied that her carelessness was assumed, and narrowly watching, I perceived that her hand trembled as she tried to steady her mace.

Mr. Bandeswyke appeared no more till the arrival of the other guests, and before that event occurred we had a dreary time of it; for Gwen likewise disappeared, and we were left to the tender mercies of her mother. I escaped after a while, and was in the act of opening the front-door to have a look at the storm, when it was hastily opened from without, and Gwen, covered by a large plaid, but wet from head to foot, stepped quietly into the hall. I uttered an exclamation of astonishment, but without the slightest word of explanation she merely bowed her head and passed on to her room. I had no time to wonder, for at that moment the guests arrived, and I was captured by my host.

The guests were dull, Harry was dull, Mr. Bandeswyke was dull, I was dull. I may as well say it at once: we were all dull, sare Gwen, who was just as usual. In spite of that, I was glad when we dispersed for the night, even while I dreaded the night.

"Let's go out and smoke," I whispered to Harry, as we stood together at the drawing-room door.

Gwen was close to us and heard. She turned back and said, loud enough for her father to hear,

"O, not to-night, do not go out to-night. It is so damp after these storms."

It was unlike Gwen. I felt annoyed. Old Bandeswyke waxed paternal on the spot.

"My dear boys, don't think of such a thing. You have no ides of our mountain air after a storm. Go to the billiard-room."

We thanked him, and vanished to our rooms. My curiosity was again roused. Why were father and daughter leagued to prevent us from going out? Of course we went.

"I wonder why they did not want us to go," said I.

"Rheumatism," said Harry shortly.

"Humbug," responded I, not more lengthily, and then added, "That might do for madam, not for master, or for—"

"Miss Bandeswyke," interrupted Harry with decision.

Then I knew what was to happen. We had talked of her as Gwen before we came to the Dumberdene.

We walked on in silence till we came to the top of the steps leading down the mountain. Then we turned and smoked in silence. It was again a gusty, fitful night. The wind was sobbing itself to sleep, like an angry child after a fit of passion, occasionally bursting forth with fresh though subdued violence, and then subsiding to a dead calm. The moon, which was at the full, was almost entirely obscured by masses of black clouds, driven wildly over her face. For one moment, as we stood under the rocky wall, the full mild light illumined the scene before us—the old castle, the mountain, the trees. Involuntarily we both started forward, for that moment had revealed to us the largest of the great cedars prostrate on the ground. In its fall a mass of foliage had been torn from the old building, which was now bared to the eye.

"The tree is fallen," I exclaimed. Again the moonlight passed away, and for a minute the darkness was dense. The old tower clock struck the hour. We counted the strokes; there were thirteen. As the last hoarse clanking sound died away, the scene was once more illuminated. Not by the moon, however. A red light blazed suddenly forth inside the ruin, exactly behind where the fallen cedar had stood. The house was on fire! A red light, a dull glowing red. We could see the flames, and we could see figures pass before them. We rushed forward. Lightest and most active, I was first at the spot. As I approached, one figure became distinctly visible as it passed and repassed before the fire. Nay, I paused in horror till Harry joined me; for though the flames were confined to one room, they were apparently beyond control, and yet this figure was plainly adding to their fury, and with a long iron rod heaping up fuel and rousing the flame. We were now so close to the house that we could see every line of the man's countenance, and it was an evil one; eyes near together, a large purple scar across the face, coarse straight black hair, a villanous expression, a dirty woollen cap with a red tassel on one side of his head, the left leg somewhat shrunk, and supported by an iron frame, the squeaking of which we heard distinctly as he limped round his diabolical work. Presently he paused, and taking up a small box scattered the contents into the fire. Its character changed in an instant to a vivid green, rendering his countenance ghastly. Apparently the heat was unbearable, for he stepped hastily back. Ha, he stumbles, tries to save himself; in vain! He falls, and falls into the very middle of that furnace, with a shriek which freezes the blood in our veins. Again we dashed forward, and the moon once more lending her light, we clambered, grasping and clinging to the ivy, straight up the old wall, and crashing through the window we stood in the burning room.

It was empty—no fire, no man! But as if to mock us, as if to prove that we had not been dreaming, a large space in the centre was lowered and bricked as if to contain a fire; a curious chimney, shaped like an extinguisher, hung over it from the ceiling; ashes and cinders, among which some charred bones were plainly visible, were scattered about, and an iron frame was lying straight across the quaint fireplace.

It was a moment never to be forgotten. We looked at one an other in silence. Even Harry was moved.

"Can we have come to the wrong room?" I whispered.

He shook his head, and pointed to the iron. Then he crossed the room, and tried a door. It was locked, but the lock was old, and we could easily have burst it, if the moonlight had not again left us in pitch darkness. "Come away," I whispered. I am ashamed to say I was trembling like a girl. My dream had thoroughly unnerved me.

"I mean to see this out," replied Harry. "Of course it is a trick. Will you fetch the lantern, or shall I?"

Both appeared equally terrible, to leave him or to be left.

"You will be quickest. I will wait," said he, in a tone which admitted no reply; and I was out of the window and scrambling down the ivy in a second.

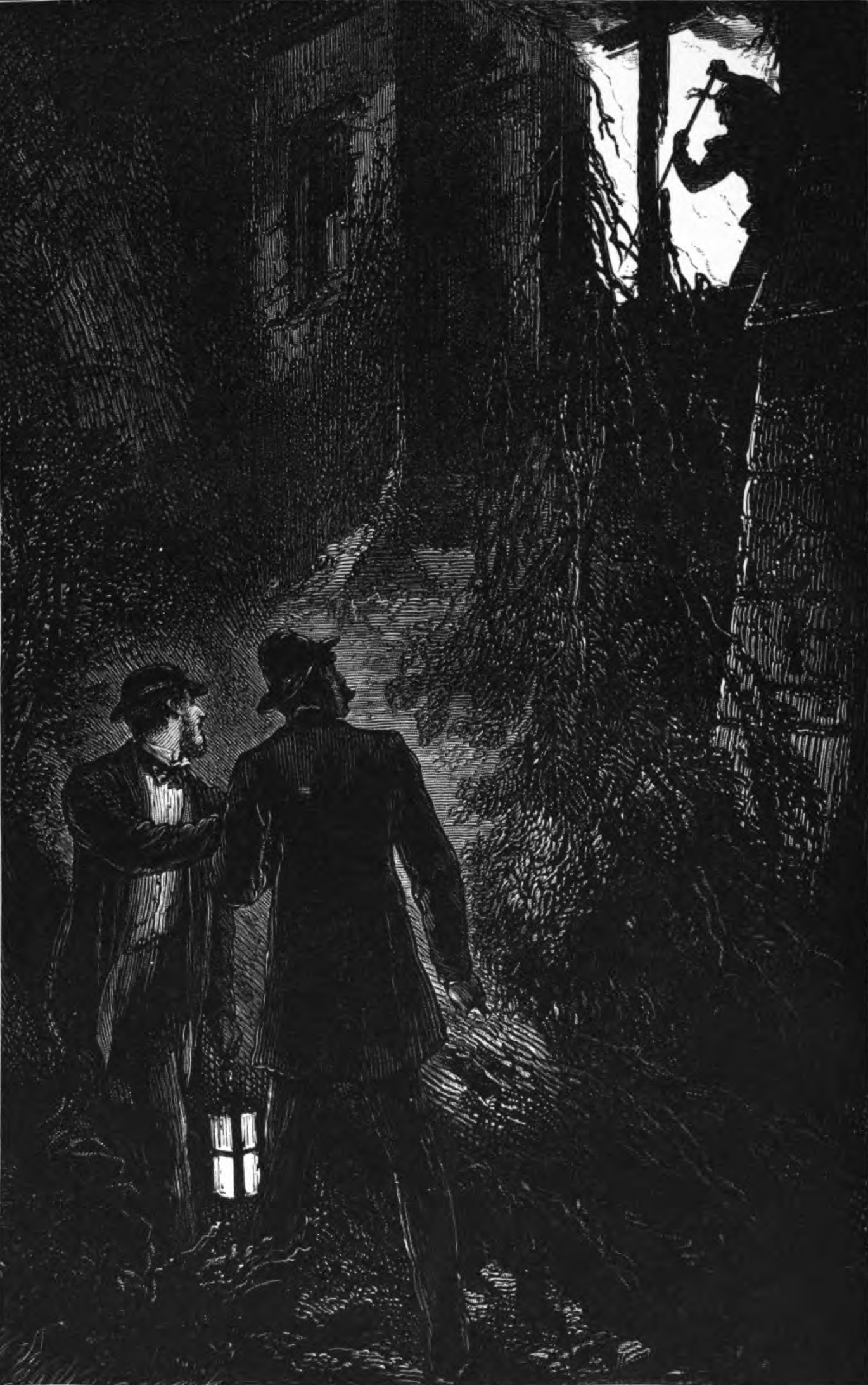

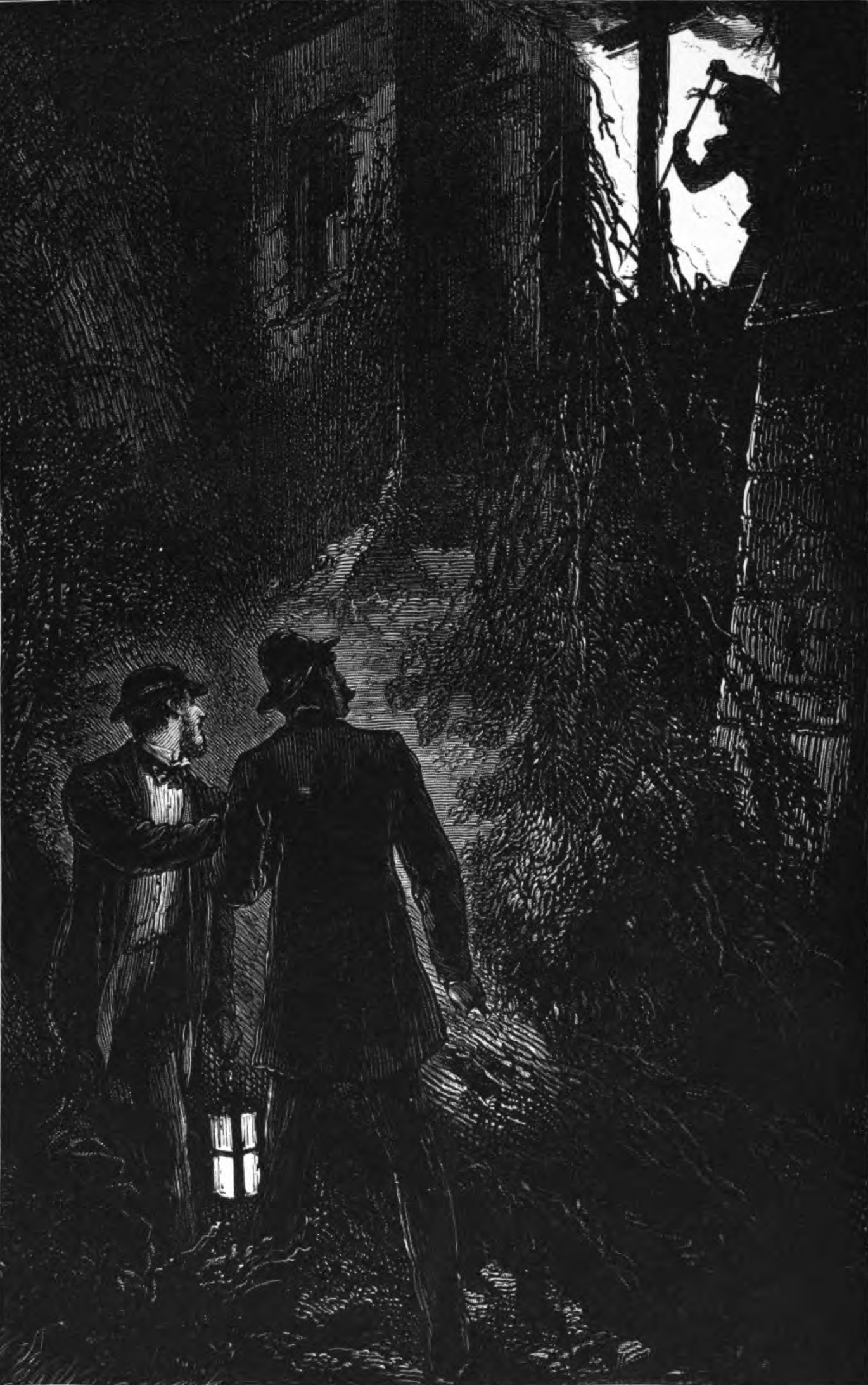

As I returned with the lantern, which fortunately we had taken out with us, I again paused in horror, for the flames were again visible, and the man with the iron was once more stirring them up and limping round them. And there, in the midst of this ghastly scene, stood my own Harry, calm, and apparently unconscious of what was passing around him. His tall figure and handsome face were as plainly to be seen as his terrible companion. It was with a sound that was more of a sob than a cry that I dashed on, tearing my hands and my clothes as I almost flew up the ivy and swung myself into the room. Then I turned faint with terror, for again it was empty, excepting that Harry stood waiting as I left him. I think he was surprised at my want of pluck. His nerves had been shaken by no previous warning, and his temperament was not excitable like mine.

We tried in vain to force open that door. Old and slight as the lock appeared, it resisted all our efforts. We paused. And then distinctly we heard a footstep approaching the other side, a halting footstep, a creaking iron. A hand was on the lock. The bolts flew back, and slowly and heavily the door swung open. We hastily raised the lantern, and stepped out into the passage. No one was to be seen. Only a sound as of rats and of falling plaster, and then all was still. Only the wind rose with a dreary moan through the loopholes above us, and passed us with a rush as it wailed down the passage. We went on, through countless rooms and passages, some wide and vaulted, some narrow and lofty, under deep archways, round massive buttresses, now down a broad oak staircase, now up steep winding steps, till our heads grew giddy. We were astonished to find the oak floors firm, and the walls, though dripping with moisture and covered with damp in places, perfectly solid. The place was safe and perfectly habitable. Why, then, was it deserted? We grew bewildered, and I was oppressed with that strange feeling that all this had happened before. Suddenly my heart stood still with wonder. It had all happened before. It was the realisation of my dream. We had turned into the picture-gallery, and there were the pictures as I had seen them, hanging, not against the wall, but from the ceiling, and swinging to and fro; all but one, the stately lady in black robes, and she was moving up and down. I almost expected her to descend and fling her robes around me, as in my dream. It was horrible to know my way as I did now. I fancied Harry looked at me with surprise as I turned with decision to the lobby on the left, and walking straight up to the projecting chimney, touched it, and then stood aside to allow the panel to fall out. It did so, and Harry followed me into a room. The room. Was I dreaming still? Harry said "No" when I asked him. Yet there it all was—the beetles racing, the "cocoons" creaking, the heap of drapery in the darkened window, the small bed in the corner, and, as we paused, we both became aware of the peculiar sickly odour, as in my dream. And of something more. There was in that room what I can only describe as the consciousness of a presence. The wind had died away in a long lull; not a sound was heard save the hoarse creaking of the "cocoons" and our own troubled breathing, and yet we both felt that we were not alone. A hot flush mounted to Harry's brow. I know that I was deadly pale. We looked instinctively towards the bed. Our eyes met. We advanced together. Again we paused. Could it be possible that we heard the faintest sound of breathing, not our own? The tattered curtains were closed; through the slits we could see something, yet we could distinguish nothing. Harry put out his hand, and gently drew them back. Yes. There it lay, that still form. The long hair covered it, and the head was turned away, as I had seen it. And as before Harry raised the head and turned the young dead face towards us, and we saw the high-bred delicate features, the old-young look, the strange colouring. And then came the long shivering sigh, the slight tremulous stretching, and the sinking back to the awful repose. And then a shriek, a woman's wail, burst forth so close, so very close, that it seemed in our very ears, and the breath that sent it forth played upon our cheeks. Without waiting for it to die away, as it did with a prolonged wail through the vaulted corridors, we rushed from the room, fled through the passages, stumbled down a staircase, and how, I know not, found ourselves safe in the open air. We never went to bed that night. We passed it in Harry's room, in wondering discussion of the adventure. Never had I seen Harry so roused. He still leaned strongly to the opinion that some trickery was at work, and with morning light grew ashamed of our panic. He resolved to relate the whole to Mr. Bandeswyke. Firm as was my belief in Harry's wisdom, I could not convince myself that all that we had seen and heard was attributable to natural causes alone.

The next morning we sought and obtained a private interview with our host, and Harry told our tale. Never did man's face cloud over as Mr. Bandeswyke's, when he began to perceive the gist of Harry's remark.

"Then, in spite of my warning, you did go out last night," was his first observation. After that he listened in silence to the end, and then he said with a smile, for which I hated him, "When the property is yours, young sir, you will probably fathom the mystery."

Harry coloured violently, but disdained to reply. I was up in arms at once. "I hope, sir, you do not for a moment do Harry the gross injustice—"

"I have heard your tale," interrupted Mr. Bandeswyke, utterly ignoring my existence, and addressing Harry: "I have heard your tale. Possibly I hold the key to the mystery. Possibly it is a mystery to me. At all events, it is as yet no business of yours, and I must request that your lips will be closed on the subject during my lifetime. You will also answer for your friend's discretion. Do you like to ride to-day?"

I fancy even Harry was nettled at this reply, and at the abrupt transition of subject, and I own that I listened with delight to his rejoinder, which was merely an announcement that we must leave the Dumberdene that day. Not only was he hurt at Mr. Bandeswyke's manner, but in my heart I felt convinced that his repugnance was as great as my own to passing another night in that haunted pile.

Mr. Bandeswyke seemed rather surprised, but received our decision with indifference. An hour later I was amused by his seeking us with regrets at our sudden departure, entreaties that we would stay, and invitations to us to join the family in Italy in the autumn. All this I attributed to Mrs. Bandeswyke, who was evidently much vexed at losing us, and I was almost angry with Harry for his cordial reception of the last proposal. Gwen was very still, very silent. So was Harry all that day, and the next, and for many days to come. He seemed to have grown ten years older in that short visit to his future home.

CHAPTER III. A FALL.

Years passed before either of us revisited the Dumberdene. Our friendship suffered no diminution, though our careers were very different. I was ordained, and succeeded to a comfortable family living. Harry married Gwen, as I knew he would. He saw a great deal of her abroad, where the Bandeswykes lived almost entirely after our ill-fated visit. The Dumberdene was shut up. At length, Mr. Bandeswyke being dead and his widow settled in London, Harry and Gwen resolved to return to the old place, with their son, a boy of six or seven. The following note apprised me of their intentions.

"Grosvenor-street, July 18—.

"Dear Charlie,—We are in England again, and mean to live at the Dumberdene. Gwen and I shall be there on the 11th. I ask you to join us as the greatest possible favour. I know your horror of the place, but the mystery must be solved. I need your help as friend and clergyman. I know more than I did. Come. Prepare to rough it, as we bring no servants at first—for reasons. We leave the boy in town.—Yours ever,

HARRY BANDESWYKE."

"As friend and clergyman." The first, of course; the second I could not comprehend, unless he wanted me to exorcise the demons, and I smiled to myself at the idea as I journeyed along. Years had weakened the vivid impressions of the time. For Harry was right; it had been a terror to me for long. I had had a severe nervous illness immediately afterwards, and for some time I could not bear to hear the name of the place.

Dear good Harry met me at the last stage; and as we wound up the zigzag to the Castle, he told me all he had heard from Gwen of the mystery, and detailed his plan, which was very simple. Gwen's father was the youngest of seven brothers, who one after another inherited the Dumberdene, and all died childless, or leaving only daughters. Their father had been a remarkable man—most remarkable; for the force of his character was such, that his directions were religiously and minutely observed after his death by every one of his sons, down to the very youngest, although the latter was but ten years old when left an orphan. They had never called him father, nor could any one of them recall a word of kindness from him. He appeared to have struck awe into their very souls; an awe sufficient to render disobedience to his wishes as impossible when he rested in his grave, and they were themselves gray-headed, as in the days when he was named among them as "the master," and when, as timid lads, they trembled at the sound of his voice. Before any of them could remember, the entrances to the older part of the Castle had been closed and barred. They had never been allowed to approach it, inside or out. Year by year the outer walls had crumbled away; year by year the foliage grew and spread over wall and mountain. Not one of the lads had dared to explore that spot.

And when the old man was dying, he called his seven sons to his side, and he made each one swear in turn that, so long as he lived and reigned at the Dumberdene, never should those barred doors be opened, never should human foot enter that part of the Castle. The oath had in each instance been kept. By degrees the building assumed the appearance of a ruin, though such was the solidity of the structure that, as we had seen, it still resisted the effects of neglect. Gwen had heard of the apparition, though she could not tell when it first made its appearance, nor had she heard any story attached to it. She knew, however, that her father had seen it. He had told her this himself, adding that he believed the codars and dense foliage had alone concealed it from others. He attached particular importance to the middle tree, which had fallen. He had also told her that the apparition came but once a year—on 26th August. "This," said Harry, "accounts for his trying to prevent us from going out that night, as well as for old Ransley's agitation. He was the only other person in the secret." Farther than this Gwen only knew that her grandfather had no hereditary right to the place. His father was a rich Dutch merchant, whose widow had become the second wife of the master of Dumberdene, the last who rightly bore that title. The first wife had left a little son, who died shortly after his father, and the property then fell into the hands of the second wife, the widow of the Dutchman. She had left it to her only son, Gwen's grandfather. He had affected the title of master, but none of his sons had assumed it. Gwen dimly remembered her great-grandmother, who had long survived her son and most of his children—a wild stern woman, wonderfully active though in extreme old age, with masses of white hair on each side of her face. Gwen had seen her pacing backwards and forwards on the terrace, regardless of wind or weather, muttering fearfully to herself, sometimes stopping suddenly, throwing up her arms above her head, or stamping her stick on the ground. Gwen was in deadly terror of her. This was all. And Harry's plan was to open one of the doors of communication between the old and the newer part of the house, and closely and attentively to examine the whole place. After that he intended to dismantle it, and either to refurnish it, or, more probably, to pull it down, and devote the space to gardens and lawns.

"I am still persuaded that the living have more to do with the mystery than the dead," said he in conclusion. "Years back there was probably some story attached to the place; but though my seven step-uncles were frightened enough to obey their father to the last, his wishes are not binding upon me, nor have they, I strongly suspect, been anything like binding upon the scamps of the neighbourhood. It is a clever trick, but I am resolved to get to the bottom of it."

And so he did, poor fellow, but not as he intended.

"But why did you want me 'as clergyman'?" I asked, returning to the point which had puzzled me in his letter.

His colour rose as of old; he half laughed.

"Well, Charlie, I daresay you will think it great nonsense, and perhaps, after all, I hardly mean it; but the child, you know. If it is a child, he must have Christian burial."

I was considerably startled. I saw that Harry's incredulity was not as perfect as he tried to believe.

Old Ransley and his wife had been left in charge of the house, and Harry and Gwen had come down quite alone, under pretence of seeing what repairs were required before they collected an establishment. They had only arrived that morning, and when we had had some luncheon, as it was still quite early, Harry proposed that we should begin our task at once.

I approach the end of my tale, the horrible end, and courage almost fails me to continue. In broad daylight on that lovely summer day we once more approached the haunted rooms—Harry, Gwen, old Ransley, and myself. We determined to enter by the upper door, that to which I had called Mr. Bandeswyke's attention on our first visit; it appeared less impregnable than the one leading from the hall. Tools were ready, but it was a long job, though Harry was a very giant in strength. At length the bars were sufficiently bent back to enable us to open the door far enough to admit us one by one. We stood in a wide lobby. Harry and I remembered it full well. He boldly led the way with his wife, who was as calm and composed as if in her own drawing-room; for was not Harry with her? We passed through the picture-gallery, where-still hanging from the ceiling, and swinging backwards and forwards, as they had swung for fourteen years and more—were the pictures we had seen before. There, too, was the one going up and down.

"Only the wind, darling," whispered Harry, as he drew her arm within his own, and hurried her on.

Why did he whisper? and why draw nearer, as if to guard her from harm? She stopped him, pointing to her of the black robes.

"How curious that this one should go up and down, Harry! I suppose it is the draught. That is my great-grandmother. Papa had a miniature copy of that picture."

Voice and manner were so entirely as usual, so unmoved, that I felt wonderfully reassured, and Harry glanced at me with a proud smile which spoke volumes.

We went on to the room. No footsteps, no creaking iron, no whispers this time. All was still; it was broad daylight. We found the panel out; probably it had never been moved since our hasty exit fourteen years before. We entered. All was as it had been. The room, low pitched and gloomy, was little less awful in the sunshine than at night. There was an indescribable oppression. We approached first the heap of drapery in the window. It was the body of a young woman. No sign of decay; but the same strange shrivelled flesh, the same light-brown hue, that we had seen before.

Gwen was now very pale, and Ransley trembled from head to foot. We turned to the bed, and drew back the curtain. There lay the little child; and when we turned the head towards us, there was the same long shiver as before, but, I thanked heaven, no scream. I could see that Harry dreaded it, by his compressed lips and by his firm hold of the little shoulder. This time the eyes half opened; there was a glimmering light in them; then another long sigh; and it is my firm belief that then, and not till then, the spirit passed away. The body did not fall back into the old position as before. It collapsed, and lay straight as Harry placed it. He called to Ransley in a low voice. The old man was on his knees on the floor.

Harry uttered an exclamation of impatience, and desired me to help him, whispering as he did so, "I was wrong, Charlie; this is no trick. There is more here than we can understand." Gently and tenderly he lifted the little child in his arms, Gwen helping him; good brave Gwen, a woman in a thousand. He bore it out of that haunted room, and laid it in the lobby outside. Then he returned for the body of the woman, and placed them side by side.

"You and I must go for the coffin," said he. "Gwen will stay with Ransley here."

"But, Harry, it will take time. Where shall we find one ready made?"

Gwen whispered to me to "trust to Harry; it was all prepared;" and again I felt that he had never been as sceptical as he tried to believe.

Leaving Gwen standing as a statue guarding the dead, and Ransley crouching near her, his head shaking as with palsy, we ran down to the hall, the great door being easily opened from the inside; a fact which we had before remarked. In the hall we found a large packing-case, out of which Harry drew the boards of a coffin, so contrived as to be easily put together. This done we lifted it, and prepared to return. And then occurred once more that episode of the imaginary door. Although I was first, holding one end of the coffin, while the other was in his grasp, I had not made many steps within the passage before he exclaimed, "Wait! wait a minute! It will be crushed. There, it is crushed! How could that door shut!" And while I saw him groping for the handle, as before, his voice grew muffled. It was but for a second, however, and then he called out in his usual manner, "All right, old fellow; go on;" and we went on to where Gwen patiently awaited us.

The coffin, though only designed for the child, was found big enough to contain both bodies. We raised our awful burden, the unknown dead, and bore it through the hall, out into the cloisters, and on to the chapel. Here, again, the extent and detail of the preparations surprised me. Not only the key of the chapel was at hand, but the key of the family vault was with it; and at a sign from her husband, Gwen placed a prayer-book in my hand, and signed to me to begin the service. I read as one in a dream. Harry, my brave Harry, my old, old friend, stood by me; his arm touched me as I read on. Gwen was at his side, a fair contrast to his firm manly figure. She was somewhat in shadow, but he stood out in bold relief under a flood of ruby light, which fell through a window behind him. There he was, a picture of life and health. Ah, how little could I divine that I was reading that burial service for the living as well as for the long, long dead!

It was over. Harry lingered ere we left the vault. We had work before us, and time lingered not; yet he paused, and with un wonted demonstration of a love too deep for utterance, he passed his arm round his wife's waist and kissed her brow; and as I walked on I heard him whisper, "My darling, you have been everything to me; be brave to the end."

Then we returned to the haunted rooms; Harry was in better spirits than at first—the worst was over. The next step was to make a thorough examination and clearance of the room whence the bodies had been removed. "We may find something more which one would not wish to become the talk of the neighbourhood," said Harry; after this search I will have the whole place pulled down, I am resolved. We began our work, drawing back curtains and opening the shutters of one window which had been quite closed. As we did so, we perceived a door hitherto unnoticed in the opposite wall. I was the first to see it, and to draw Harry's attention to it. He was the other side of the room, but he instantly advanced towards it. Suddenly he stopped, and once more I saw that groping motion of his hand.

"How very odd! There can't be a door here," said he.

For the first time Gwen's composure left her. She sprang to his side; she clasped his arm.

"A door, Harry! Not a door—O, say it was not a door!"

She was pale and trembling; he quieted her in a moment. There was nothing to fear, he said; but as she unclasped his arm and turned away, I heard her murmur, "The first time, the first time!"

O, why did she leave him then, why did she turn away? He stepped forward to the spot I had pointed out.

"Yes," said he, "this is plainly the way out."

What was that noise? What next met our horrified gaze? There was a creaking and crushing of planks giving way; the spot on which he stood failed beneath him. He clutched wildly round with his hands. We sprang forward to save him. We touched him; we almost grasped him. He slipped from our hold. For one moment we looked on his agonised face as, with one cry, he fell—gone from our sight for ever. And the boards rose and fitted into their places with a snap, and all was firm and solid as before.

For one moment I believe I was mad—so sudden and so awful was the shock. I tore wildly at the flooring with my bare hands, and called loudly on his name-called to him to return. It was Gwen who brought me to myself—Gwen, Harry's wife, nay, his widow. She drew me back, her face distorted with horror, yet her senses alert and under command. Her voice was hoarse and grating.

"The room below—the room where you saw the fire; he has only fallen through. Come; be quick!"

She would believe it, she must believe it. She drew me on; it was a ray of hope. We rushed across the lobby and down the stairs. Five minutes before he had been with us on those very steps; where was he now? The room below, all the rooms near, the passages, all were empty. The fatal thickness of those walls, what might they not conceal? We called him—there was no reply; and as we stood and listened, the rich flood of sunshine fell on our white faces, and we heard the joyous song of the birds and the voices of the gardeners outside.

"There must be a hiding-place in those walls," exclaimed Gwen. "The tools! fetch the tools! I will go back and stay with him till you come."

"Stay with him!" Never again, Gwen; never again. It comforted her to say that, and she went back to the room. I fetched not only the tools but the men, and in a few minutes a ghastly secret was laid bare.

"It is hollow, sir," said the man who dealt the first stroke.

It was hollow. A hole about six feet in circumference descended—ah, how far?

I had to hold Gwen back with all my strength, she leaned in so far, as her voice shrieked down the fathomless abyss,

"Harry! my Harry!"

Shall I ever forget that cry? Did it reach his ear? There was no answer, no sound from below. Then she raised herself up, stretched both her arms before her, and with one cry of despair fell back into a dead faint. Poor thing! it was the best thing that could happen to her then. We carried her down and gave her over to Mrs. Ransley's care, and as soon as I had sent for a doctor I returned to the room. They were trying to fathom the abyss, and trying in vain. It seemed to descend to the very foundation of the building. Lights had been lowered and extinguished by the foul air. All hope was of course at an end; and when at length the lights burnt steadily, there was that revealed which told of a fate so awful that strong men who stood by turned sick and faint.

The sides of that awful hole were, after a certain space, jagged and uneven. Sharp stones, pieces of iron, hooks, scythes, and knives were let into the wall with such diabolical art, that any one falling must have been fearfully mangled ere he reached the bottom; and sickening marks of such a fall were there. Nothing but the utter demolition of the building would enable us to recover all that remained of him who half-an-hour before stood among us in life and health.

The demolition was ordered. The building was to be razed to the ground. Gwen would have had the work continued night and day; she hoped, hoped madly, long after hope seemed impossible. But men must eat and sleep, even though widows' hearts are wasting and breaking beneath the load of agony. And when days grew into weeks, and little apparent progress was made, then, and not till then, did Gwen consent to leave the place. She went to her mother in London. We hoped that her child would rouse her from her grief and bring her back to life, but it was not so. A strong nature is not always an elastic one; she had received a shock from which she had not power to rally. Her heart was broken. She meekly did what she was told to do, and no more. Never again was she seen voluntarily to open a book, or to take any kind of employment in her hand. She only sat and waited the summons, which came ere many weeks had passed, and then the weary spirit was set free. But I am forestalling my tale.

I cannot tell what we found when at last the work of demolition was completed. Gwen was at rest before that, and as I followed the remains of my best, my only friend from the Castle (for he was taken to his father's home), I called to mind with bitterness our first entrance within those walls destined to be so fatal to us both.

I saw Gwen often during the weary interval before her death. I was the only person who could rouse her even for a moment from her lethargy. When she had ceased to hope, she only once alluded to the past. Some old papers had been found in the picture gallery so often described, and as they threw light on the mystery of the haunted room, the doctors hoped they might rouse her. For the moment she was roused—not to listen to the tale of black wickedness unfolded, but to give me one warning, one charge regarding her boy—my ward. She told me that the appearance of an imaginary door was an event of usual occurrence in her family before a death. Her father and all his brothers had seen it, but she added it had been seen three times in each instance, and with intervals of years between. "I felt little fear, for he only saw it once," said she. It was the only time she spoke of Harry. I did not undeceive her.

She had with rare courage kept the knowledge of this tradition from her husband. She hoped, she said, that it was only a superstition, and would die away if not fostered. She desired that her boy might never hear of it.

The papers were curious. They comprised two or three letters and an old MS. book—journal, account-book, receipt and cookery book all in one, as was the mode of our ancestors. It was the private note-book of her of the black robes—the second wife of the master of Dumberdene. The story was told more by the extraordinary nature of the receipts, and by the entries in the portion devoted to accounts, than by any regular journal. The book seemed to have been commenced before the death of her first husband, for it began with sundry commonplace entries respecting the expenses of his somewhat long illness. Then we have his funeral, and her journey to England with her little son. A short stay in London, where she probably met the master of Dumberdene, for the various items of a trousseau occupy the next few pages; and then follow the usual small expenses of a lady in a country house. All this is interspersed with recipes for soups and puddings, possets, cures for small-pox, and various other matters of the kind. Up to this point I had been obliged to call in assistance to decipher the text, for though the writing was legible enough it was in German and Dutch. But after a year or two passed at the Dumberdene, the lady had apparently become sufficiently at home in the English language to adopt it as her own, and all difficulty on my part was at an end. Her second husband soon appeared to be in failing health, for by degrees it becomes plain that the management is vested in her hands. The payments became more those of the master than of the mistress of the house, and about this time the recipes are of a strange nature. Next to a sleeping draught of a very mild character, we have one containing stronger narcotics, and a note underlined, to the effect that this should on no account be given to children or young people, as it would prove fatal, though not at once. A short extract follows, from some old treatise on poisons, and then one or two recipes for poisoning animals without injury to the skin. Shortly after this comes the funeral expenses of the master of Dumberdene, and a short expression of desolation at this second widowhood, with the additional burden of the young master to bring up with her own son.

The amount of medicine the poor young master swallows after this must have gone far towards relieving her of that burden. Then comes a curious and significant item. So much to a person called Johed Burkdorf for his journey, and that of his niece Santje, from the former home of the widow in Holland. Then an expression of joy at having once again the society of her old tutor and friend. What precise position this Johed held in the household is not clear. Ere long all payments pass through his hands, and if he acts as tutor to the lads, he evidently performs also many services which rather fall to the steward or bailiff. Santje's position is more clearly defined. She is what would now be termed nursery-governess. She waits on the children, and teaches them; and we learn that the young master, the delicate highbred English boy, wins her heart at once, whereas there is deadly feud between her and the fierce young Dutchman. About this time two circumstances of importance are to be noted. First, the family moves into the modern portion of the house, and the older part is deserted, though the lady reserves one room there for herself, and passes much time there in trying experiments with Johed. Secondly, the results of these experiments are noted down. Johed now comes out as a chemist, and the room is a laboratory. It is altered to facilitate their work. A curious chimney is built, to enable them to try an experiment which is set down at full length. Certain chemicals are to be thrown into a furnace. Any animals shut up in a room above this will be not only rendered insensible, but reduced to powder. If the fire is extinguished too soon, life may be preserved for centuries, though consciousness will never return. In human beings the flesh would wither and the skin assume a light-brown hue. This was the theory set forth.

It was impossible not to interpret this diabolical recipe by the light of recent discoveries. But the letters to which I have alluded make the tale of horror yet more clear. They were mere scraps in Dutch and broken English, evidently written by Santje, who, I doubt not, was the young girl over whose mortal remains I had read the burial service on that sad day. She appears to have been shut up in the old part of the castle with her charge, the young master, and I conjecture that these letters, by which she attempted to make known their danger, fell into the hands of Johed and his mistress, for they were all found in the MS. book. They contain short entreaties for help, and in one we have a hasty notice that they are moved to the Dumber room, and, on pretence that the master's illness is an infectious fever, are excluded from all intercourse with others.

"No one comes to us but my cruel uncle," writes the girl, "and I dread the squeaking sound of his iron leg along the passage."

From these documents it was not hard to trace out the tale of crime and sufferings. Had confirmation been wanting, it was found in the will, which left all to the widow should the young master die under age; and in the coffin found in the family vault with his name and the date outside, inside a carefully-weighed freight of wood and bricks.

If the wretched Johed did actually fall into the furnace which he was piling up for others, who can wonder that his accomplice should lack the courage to enter the room which she had made a grave? Who can wonder that she had the building barred and closed, and that she did her utmost to make this state of things binding upon her son and his descendants? Who can wonder that a curse rested upon the house? Whether she knew of the fearful oubliette over which she had placed her husband's son, we shall never know. There is no mention of it in the MS. Its antiquity proves that she neither planned nor completed it, and we may hope that she had never discovered it.

I have never again revisited the Dumberdene. Beautiful grounds now cover the spot where once the haunted rooms rose in their masses of foliage. A fountain now plays over what was once a grave. Harry's boy lives in the more modern castle, which we left standing. He is always asking me to stay with him there. But I cannot face those memories. My trust is that the curse has died out,—dare I say has been expiated?—and that I alone am in possession of a secret so fearful, that there are hours when I could almost doubt if memory has served me rightly.

The above story is in the public domain and can be copied or distributed freely. Credit to this site appreciated, but not necessary.