Some years ago, through the interest of a relation, I received the appointment of a lighthouse-keeper. I did not much care about the work, as I dreaded its dulness; but I was young and beginning the world, and could not afford to be nice in my selection of an occupation.

The remarks of my friends, when they heard of my new career, were certainly not calculated to reassure me. Most of my companions were in one way or the other connected with the sea, and all the congratulations I got upon my advancement in life were ominous shakes of the head, and muttered remarks as to there being "queer tales about them lighthouse chaps;" the concluding practical advice being generally, "I wouldn't take it, if I was you, Tom."

This was certainly rather calculated to throw a damper upon my new employ; but, as I argued with myself, if I did not take it, I had nothing better to look to, and I would not throw myself upon my friends; so, determined to make the best I could of the matter, I went down to Blackwall to be instructed in my new duties. It was not long before I made myself sufficiently acquainted with them as to be au fait at the management of the lamps and apparatus; and was at length pronounced fit to undertake the duties of supernumerary lighthouse-keeper.

These supernumeraries have to hold themselves in readiness to proceed to any part of the coast where they may be required to relieve others who, from sickness or other causes, are removed from their posts. A few mornings after my instruction was completed, I received a sudden intimation that I was required to proceed to take charge of a lighthouse on the coast of Wales. On making inquiries about the new charge to which I was posted, all I could learn was, that the legitimate keeper had deserted his employ some months before, and had not since been heard of; that his place had been temporarily filled-up by a man from a neighbouring village, who it was hoped would have continued in it; but that he had recently insisted upon giving up his berth, alleging as an excuse that the dulness of the life was more than he could bear. With this information (which was all the people at head-quarters either could or would give me), I was forced to be content, and started off for Wales that very afternoon, arriving at the scene of my future labours on the next day. At the first glance, the prospect was not alluring. It was at the end of October, on one of those dull, boisterous, dank days on which all Nature seems mourning the brightness of the summer that's past, and lamenting the rigour of the winter to ensue. The wind came sometimes in strong chill puffs, that seemed to send the cold to one's very bones; sometimes in soft sighs that moaned dismally through the half-barren trees, sending the leaves slowly fluttering from the branches to rot upon the oozy ground. The desolation of the scene seemed even to have infected the few cottages by which I was surrounded, and in which the only signs of life appeared to be clouds of steam (evidently from washing) which came through the open doors; while a few slatternly women went in and out on pattens, sometimes chiding the groups of children that clustered on the threshold, greedily eyeing the pools of mud and water beyond.

Even had I wished to possess it, I saw that there was little information to be got there; and as I was tired with my journey and anxious to be out of the cold as soon as possible, I put what effects I had into a boat (which I hired with some little difficulty), and set off for the lighthouse, which was built upon a rock at some distance from the land. On the way thither I thought that the boatmen eyed me somewhat curiously, and were not very talkative, simply hailing my volunteered information that I was the new keeper with an "Ah!" and a significant glance at each other. I did not notice this much, however, as I was occupied with my own thoughts, speculating how I should pass my time in the grim building I was approaching, round which the eager waves leapt, as if anxious to engulf it, curling back with a sullen roar at their defeat. On my arrival I was received by the man whom I was to relieve with evident satisfaction. He was a gaunt beetle-browed Welshman; and I could not help noticing the haggard anxious look his face wore. Almost the moment I set foot in the building he called out to the boatmen who had brought me to "wait, as he wouldn't take long setting his new mate to rights with the place, and they could take him on shore." This, however, I combated stoutly, and insisted on his at least keeping me company the first night, as I did not know how the lights worked: to this, after much demur, he consented, with evident reluctance, and the boat went back.

My new abode consisted merely of the "lantern," in which the lights burned, and, beneath, the watch-room, furnished with a bed, chair, and table, and such culinary and domestic necessaries as the keeper required. A flight of stairs led to the door by which the building was entered, and a lower flight seemed to lead to cellars or recesses of some sort; my companion did not, however, show me these, as he said they were never used, and it wasn't worth while going down in the cold. The evening drew quickly on; and as the autumn twilight grew darkling over the waters, the sea and wind both seemed to rise, and the crash of the breakers as they leaped fiercely up the rock, and the whistling of the gale, were anything but agreeable adjuncts to a residence desolate enough in itself.

For the first hour or two of the evening I was busily enough employed in learning how the lamps were trimmed, lighted, &c., and in reading the regulations by which the keeper was to be guided. When I had, as I thought, made myself sufficiently acquainted with the routine of the life that was before me, I sat down with my quondam companion (whose name was Morgan); and as we smoked our pipes by the fire, tried to gather from him the particulars of the late keeper's disappearance, and why he himself was giving up the situation. Morgan, however, was anything but communicative; he said he knew very little about his predecessor; he was a sulky gloomy sort of chap, who lived here with a very pretty wife, and was said to drink hard at times (but that he didn't know about). One night the lamps were not lighted; and when the coastguard put-off to see what was amiss, the lighthouse was found deserted, and as a good many metal articles of value were missing, it was supposed that the keeper and his wife had stolen them and made off. As for himself, he had lived there better than three months, but it was so mortal dull, he couldn't stand it any longer. This was all I could get from my new friend, and even this was only got out of him by close questioning.

As the night wore on, I noticed that Morgan seemed to grow fidgety and uneasy, and applied himself, rather more than I thought the authorities would have approved of, to a case-bottle of spirits on the table. It seemed to have no effect on him, however; and he at length volunteered to look after the lights that night, so that I might have a good rest after my journey. I was too tired to gainsay this, and in spite of an uneasy feeling, which I could not account for even to myself, soon fell into a troubled sleep. Whether it was the novelty of my situation or not, I hardly know, but during the first portion of the night I scarcely slept half an hour consecutively; and when I awoke, hearing the never-ceasing roar of the waves, contrasting with the deep silence within the building, I always, in spite of myself, began wondering why the last keeper had left, what sort of a woman his wife was, and whether he had really stolen the missing things. These speculations seemed so absurd, that I tried hard to dismiss them, but without success; and it was only as the dawn was breaking that I fell into a deep unbroken slumber, from which I did not wake till the morning was far advanced.

When I arose, I found it was a bright fresh morning, the gale having died away to a soft south-west wind. As I stood by one of the open windows, how different the scene appeared to the gloom of yesterday! Where the sunlight fell upon the still heaving billows it turned them, now to masses of sheeny opal, now into cascades of diamonds, as the spray was thrown high into the air. In the distance, like snowy sea-birds, appeared the white sails of the fishing craft; and as the fresh wind cooled my fevered cheek, my spirits rose wonderfully, and I anticipated almost with delight the calm hours I might spend here with my books, surrounded by the ever-changing beauty of the ocean. Morgan now came down from the "lantern," and pointed to the breakfast he had got for me; his own, he said, had been finished long since, and as soon as I was ready he would go on shore. Although I could not help being surprised at the almost nervous haste the man displayed to be off, I now had nothing to urge against it. I therefore finished my repast as expeditiously as I could; and having lowered the boat attached to the lighthouse, we pulled on shore almost in silence. When within about half a mile of the land, Morgan, who had been thinking deeply, suddenly stopped pulling, and very abruptly asked me if I had any arms in the lighthouse. Somewhat startled at the question, I replied that I had a revolver, but it was unloaded, as I didn't see how I could require it. "Better load it," was the hurried answer; "it's lonesome at times out yonder, and you'll feel more comfortable if you've something by you as you can trust to." We were close to the land now, and in a minute or two my companion sprang ashore, and hurriedly wishing me good-bye, strode away through the trees, and was soon lost to sight. I knew no one in the little village; so thought I would go up to the coastguard station, as I had been desired to put myself under the orders of the officer in charge. There was no one there, at the time I arrived, but an old man-of-war's-man, to whom, however, I duly reported myself, and got him to give me some information as to where to get my provisions, &c. This he very good-naturedly did; and while going down to the village, I questioned him about the late keeper's desertion, which somehow or other always seemed strangely to interest me. My new friend, however, could tell me no more than Morgan had, viz. that the man and his wife were supposed to have stolen the articles that were missing, and decamped. I spent a good bit of the afternoon in making my little purchases, and returned to the lighthouse about four o'clock, in order to be in time to light the lamps before the approach of dusk. After the boat was securely fastened up, and the door locked and barred, I must confess that a dull sense of loneliness fell upon me. I shook it off, however, and busied myself with my work; and what with trimming the lights, and preparing and discussing my evening meal, I got through the time pretty well till eight o'clock, when I went up into the lantern to see that all was working correctly, and then sat down to commence my first night's watch, alone in the midst of the waters.

All anticipated evils seem smaller when really near. I had all along so much dreaded the dulness of my night-watchings, that now I had really commenced one of them, I was agreeably disappointed at finding it much more endurable than I had expected. There was certainly an oppressive silence reigning through the building, and the monotonous boom of the waves dashing against the rock was not inspiriting; but I had letters to write home, plenty of books to read, and my lights to visit every hour; so that altogether the night passed quickly enough away; and when the dawn broke, I went to bed with the hopeful exclamation that "it wasn't so bad, after all." The following day was Saturday, and I determined to devote it to putting my room in order. I did not rise till nearly two o'clock, and spent the remainder of the afternoon in arranging my books, clothes, &c. As the evening drew on, I trimmed and lighted my lamps, and then read till nearly nine. About this time I began to find a difficulty in confining my attention to my book. In spite of myself, my thoughts kept wandering to their old theme—the late keeper's desertion of his post, and what sort of a life he had led in the room in which I was sitting, to induce him to disappear so mysteriously. I roused myself, by a strong effort of will, from these profitless speculations, and went to the window to see what sort of a night it was. There was no moon, and as far as the eye could reach, nothing was visible but the black heaving waves purposelessly swaying to and fro, sometimes tinged by a faint streak of phosphorescent light, as the white ridge in which they culminated rippled slowly away. It seemed very lonely to be built up there in that waste of waters, and a sort of cold chill seemed to settle on my heart as I began to revolve all sorts of improbable contingencies, such as having a fit, or the lighthouse taking fire. Altogether, I felt myself gradually getting into such a state of nervous excitement, that I could hardly bear my own thoughts. So, determined, if possible, to break the spell that seemed creeping over me, I mixed a stiff glass of grog, and sat down with my pipe by the fire. There was nothing to disturb my thoughts, and I sat conjuring up all sorts of home scenes, listening absently to the half-minute click of the lights as they revolved above, the only sound that broke the dead silence surrounding me. The clock had just struck eleven, and I was thinking of visiting my lights, when suddenly a confused noise of struggling and curses, intermingled with the sound of heavy blows, arose from beneath me. I sprang from my chair, my first impression being that thieves had broken into the lighthouse. While I stood listening, rapid steps ascended the stair; and as I turned to seize the poker as the nearest weapon available, the door flew violently open, and to my intense horror, the sound of oaths and struggling commenced close by me, but not a thing which could cause it was visible! The noise barely lasted a minute, lifetime as it seemed to me, and appeared again to descend the stair. For a moment all was still, and I was beginning to try and persuade myself that I had been the victim of some horrible hallucination, when a wild shrill scream, the agony of which haunts me still, rang through the silent building, and a woman's voice exclaimed, "George, George! for God's sake don't murder me!" A dull thud, as of some heavy sub stance falling to the ground, a low gurgling noise, and all was still.

Palsied with horror, I stood leaning on the chair to which I had clung for support, every nerve strained in agenised expectation of a renewal of the disturbance; but minute after minute went by, marked by the sound of the revolving lights, and all remained as still as the grave. Little by little I recovered power over my thoughts, and sat down, trying to account for the scene I had just gone through. Could any joke have been played on me? That hardly seemed possible, for I had barred and locked the door myself, and the key still hung beside me. I could scarcely bring myself to believe it was anything supernatural, for I had been all my life a sceptic as to such things; but how to account for the scuffling in the room close by me? I at length became more emboldened by the perfect quiet that reigned, and got out my revolver and loaded it carefully, and summoning up all the resolution I possessed, determined to go down and examine the cellars where the noises had apparently begun and ended. Taking a closed lantern in one hand and my revolver in the other, I cautiously descended the stair, looking around and behind me, I must confess, with fear and trembling. Nothing extraordinary was, however, visible; the door was barred and fastened as I had left it, and all the things that lay about were in precisely the same positions as when I had seen them last. Not a sound was to be heard but the dash of the waves, which broke upon the walls around and above me now. I was somewhat reassured by finding everything as I had left it on coming in; but as I prepared to descend the lower winding stair leading to the cellars, I felt a smothered sensation upon my chest, and my heart beat so loud that it would have been audible to any one standing near. Down the narrow stair I went cautiously, the air becoming colder at every step, while the little light that came from the lamp I carried showed that the walls were dank with moisture, and covered with fungoid growths. When I arrived at the bottom, I found myself opposite a strongly-built door, not apparently fastened. The clammy sweat rolled down my face, and it was some minutes before I could summon up enough courage to thrust the door open with my foot. Holding the lantern forward, but almost dreading to see what its light might reveal, I found that two or three steps led down to a large cellar, made apparently in the rock itself. The walls, like those surrounding the stair, were dripping with moisture, and a peculiar earthy sickly odour seemed to taint the air; but, with the exception of some billets of wood, a chopper, and a large hammer thrown into a corner, the place was perfectly empty. I satisfied myself that there was no outlet to it; and barring the door as best I could, returned to the watch-room slightly relieved in mind, but more puzzled than ever to account for the scene I had gone through an hour before. I passed the remainder of the night in the "lantern;" and may no one ever know such wretched hours as dragged their weary length along till dawn!

Out of the chaos of thoughts that went whirling through my brain, I determined that, as soon as daybreak released me from my watch, I would instantly go on shore and inform the officer of the coastguard of the whole affair. At about eight o'clock I securely fastened up the place, lowered the boat, and taking advantage of the light wind, sailed on shore, went straight up to the coastguard station, and asked to see the officer. The men gathered, I think, from my haggard looks and flurried manner, that I had something of importance to communicate; and one of them took me at once to the officer's cottage, which was not far distant.

Mr. Thomson, who commanded the coastguard, was a man of about thirty-three years of age. He had been a lieutenant in the navy, and was now on half-pay. Being without private means, and seeing no immediate prospect of active employment, he had petitioned and petitioned the Admiralty until they had given him his present appointment; and the men who served under him said there was not a braver or better officer in the whole service.

After I had told my story exactly as the circumstances which gave rise to it occurred, Mr. Thomson gave me a keen searching glance, and very abruptly asked me what stories the man I had relieved had been putting in my head.

I replied, none; that he was very uncommunicative, and would hardly give any reason for leaving, except that the life was so dull.

"Very well," was the quick answer; "I'll give you a man to stay a few days. Some one has been hoaxing you, or, more likely still, you've dreamt the whole affair.—Here, Wilson, you must go off to the lighthouse for a few days; this man here thinks he's been hearing ghosts, or some nonsense of that sort, out yonder. You'd better go with him, and show him what rubbish it is; for I think you fear neither man nor devil."

"Well, sir," was the reply, "as regards the devil, I never come athwart his hawse yet, thank God! but I do hope, by the aid of a fair conscience, as I shouldn't miss stays if I did."

"Very well," was the reply, that's settled.—Wilson will keep you company for a few days, and I hope I shall hear no more of the matter. No doubt you had a bad nightmare; and I'd recommend you to keep a sharper eye after your lamps, and then it won't occur again. That'll do."

With this curt decision we were dismissed, and Wilson (who happened to be the man to whom I had spoken on my first arrival) and I strolled to his cottage to get what things he required while with me. On our way I retold my story; and although he was evidently incredulous as to its being anything but a dream, he asked me to say nothing of it to his wife, who was very poorly. His wife evidently did not relish his going, but there was no disobeying the orders he had received; so, after having our dinner at his cottage, we returned together to the lighthouse. Everything was in its place as I had left it, and when we explored the cellar together, the same fastenings were upon the door that I had placed there the night before. However, we now nailed it closely up; and the evening, enlivened by Wilson's sea-yarns, passed quickly enough away till twelve o'clock, without anything occurring; and after that we agreed to take alternate two-hour watches in the "lantern," Not a sound broke the stillness all night; and as we sat down together to breakfast in the morning, I received the bantering of my companion upon my dream, as he called it, with an uncomfortable sensation of having made a fool of myself.

The days passed away thus till Thursday, not a single event occurring out of the common, and I had by this time thoroughly persuaded myself that I had fallen asleep and dreamt all the horrors about which I had made such a stir. Towards noon on that day, a boat came off with a message for Wilson, to the effect that his wife had had a bad epileptic fit the night before, and was then very ill. I could not offer any opposition to his departure under such circumstances, and had even so well recovered my ordinary nerve, that when he asked me if he should send another man to take his place, I said no; all the noises I had heard must have been the effect of imagination, and I was quite content to remain alone. So he went off. Friday, and Friday night, passed quietly enough, and on Saturday morning I was obliged to go on shore to get some provisions I wanted. I was doubtful at first whether I would go, as the day was dark and louring, with heavy banks of leaden-looking clouds to windward, which betokened a coming gale. However, I determined to risk it, and make as much haste as I could; and taking advantage of the wind (now rising every minute), was only away about two hours. On my return, I made all due preparations for a stormy night, doubly barring the doors and putting battens on all the lower windows. After the lamps were lighted, I stood for some time at one of the windows above, watching the warring of the elements. The black scud flew across the heavens as though rushing in terror from the fierce wind that howled across the waters, and the sea seemed turned into a gigantic caldron of seething foam, save when, like monsters arising from the deep, the huge black waves met each other with a furious roar, the foamy atoms into which they dashed themselves glistening in the murky night, till swept away by the wind.

The scene was a grand one; but, with a feeling of compassion for all in distress at sea that night, I turned to the more congenial view of my bright little fire, beside which I now sat down and smoked till nearly ten, arousing myself at that hour to write a letter of some importance to my brother. The subject upon which I was engaged had reference to some accounts which I had examined for him some time before, and respecting which he had written to me. The letter necessarily contained a quantity of figures, and I was so deeply engaged upon them, that I paid no heed to the flight of time, till, with a sense of horror amounting almost to sickness, I heard the sound of oaths and blows emanating from the cellar. A moment's pause, and the footstep I had heard before ascended the stair; and as I crouched into a corner, with eyes dilated and every hair upon my head moving in my agony of terror, the sound of scuffling commenced close by me, though, as before, not a thing was visible. Again the sounds appeared to descend the stair; again, above the howling of the wind and the roar of the waves, arose the agonised entreaty, "George, George! for God's sake don't murder me!"

How I passed the remainder of that night, I hardly know. Nothing more occurred; but I was so unstrung by what I had for the second time heard, that I remained, Heaven knows how long, crouching by my bedside, muttering incoherent prayers, and in a state of hysterical fear which almost bereft me of my senses. With the first streak of dawn I prepared to go on shore, at great risk to myself; for though the sea had been somewhat beaten down by a heavy fall of rain, it was still much too rough to be quite safe for a small boat with only one man to manage it. However, I got safely on shore, and instantly went direct to Mr. Thomson's cottage, and told him what had taken place for the second time.

"This is very strange, my man," he said, eyeing me with no particular favour. "This thing happened to you when you were alone before. I give you a man I can trust in, and nothing takes place while he is there; but the moment his back is turned, you come to me with a cock-and-a-bull story, which I tell you candidly I don't believe."

I replied that he might believe it or not, as pleased him; that I had told him nothing but the truth; and begged to be allowed to give up my situation at once, as, I said, no earthly consideration would induce me to pass a night alone again in the lighthouse.

He looked hard at me for a moment, and then said, "Of course it is your own fancy; but something has evidently frightened you. I will try you once more, and get Wilson to stay with you this next week; and next Saturday night I will myself come off and stay with you."

We went down together to Wilson's cottage; and although his wife was still very unwell, Mr. Thomson got him to agree to come off with me at once, and stay the next week, and on the Saturday he himself would join us.

We returned to the lighthouse at once, Wilson in no very good temper, and evidently thinking me a cowardly fool, or that I was hoaxing him. When we got off, he insisted on going down to the cellar with me. Everything was as we had left it, save that the door, which we had fastened with long nails, was ajar, the nails seeming to have been wrenched from the wood! I at once assured my companion that I had never been down the steps since he was with me. He heard me in silence, but with evident incredulity; and together we fastened up the door in such a manner that nothing short of sledge-hammers would open it, and returned to the watch-room.

The days and nights went quickly by, nothing occurring to alarm or disturb us in the slightest degree. Wilson recovered his good temper on hearing that his wife (to whom he was deeply attached) was much better, and proved himself, as before, a most entertaining companion.

At about four o'clock on Saturday afternoon Mr. Thomson came off, and asked us banteringly what we had heard.

The reply of course was, "Nothing."

"Nor ever will," was the answer. "However, I'll look-out with you to-night."

He then questioned me closely upon the exact situation and description of sounds I had heard, and minutely examined the whole place. The fastenings of the cellar-door were not removed, but an additional padlock put on, as also on the lighthouse-door.

Mr. Thomson then said that, as the sounds appeared to begin and end in the cellar, towards eleven o'clock we would post ourselves, armed with revolvers, opposite the door, and wait the event. I certainly did not much relish the prospect; but the other two seemed so cool and confident, that I could make no demur. We passed a pleasant evening in the watch-room, till, at twenty minutes to eleven, the revolvers were carefully looked to, and, with a large ship's lantern throwing out a brilliant light, we descended the spiral stair in a body, and hanging up the light, waited what might ensue. It was a very calm night, and the gentle ripple of the waves against the rock was barely audible, and so profound was the dead silence, that we could hear the slow monotonous ticking of the clock in the watch-room. As we stood and waited, we knew not for what, in almost the foundations of that lonesome building, the minutes seemed like hours, as we eyed each other and the damp grim walls around. Suddenly the little bell of the clock in my room rang out eleven, and during the minute or two that ensued we held our very breaths in expectation.

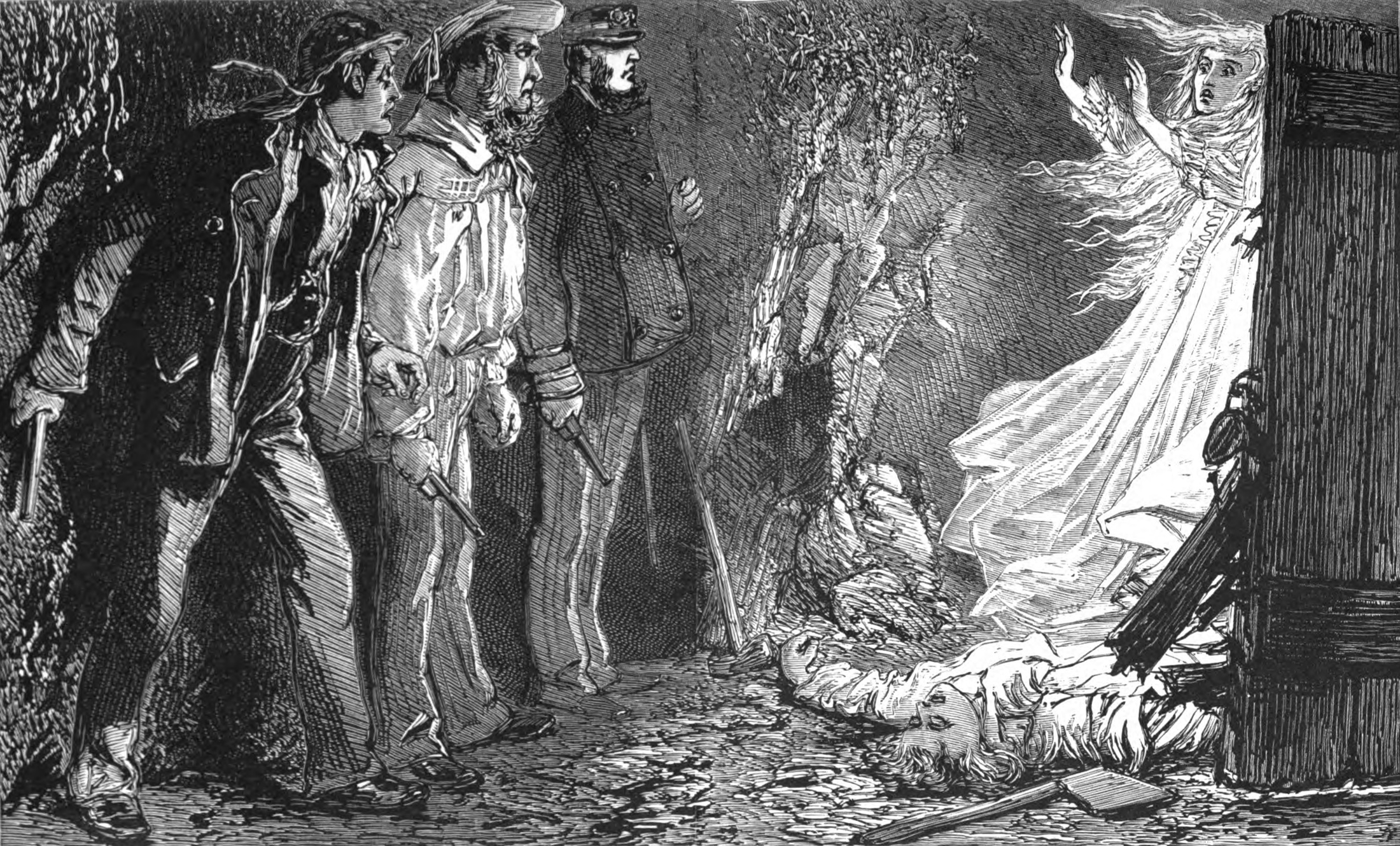

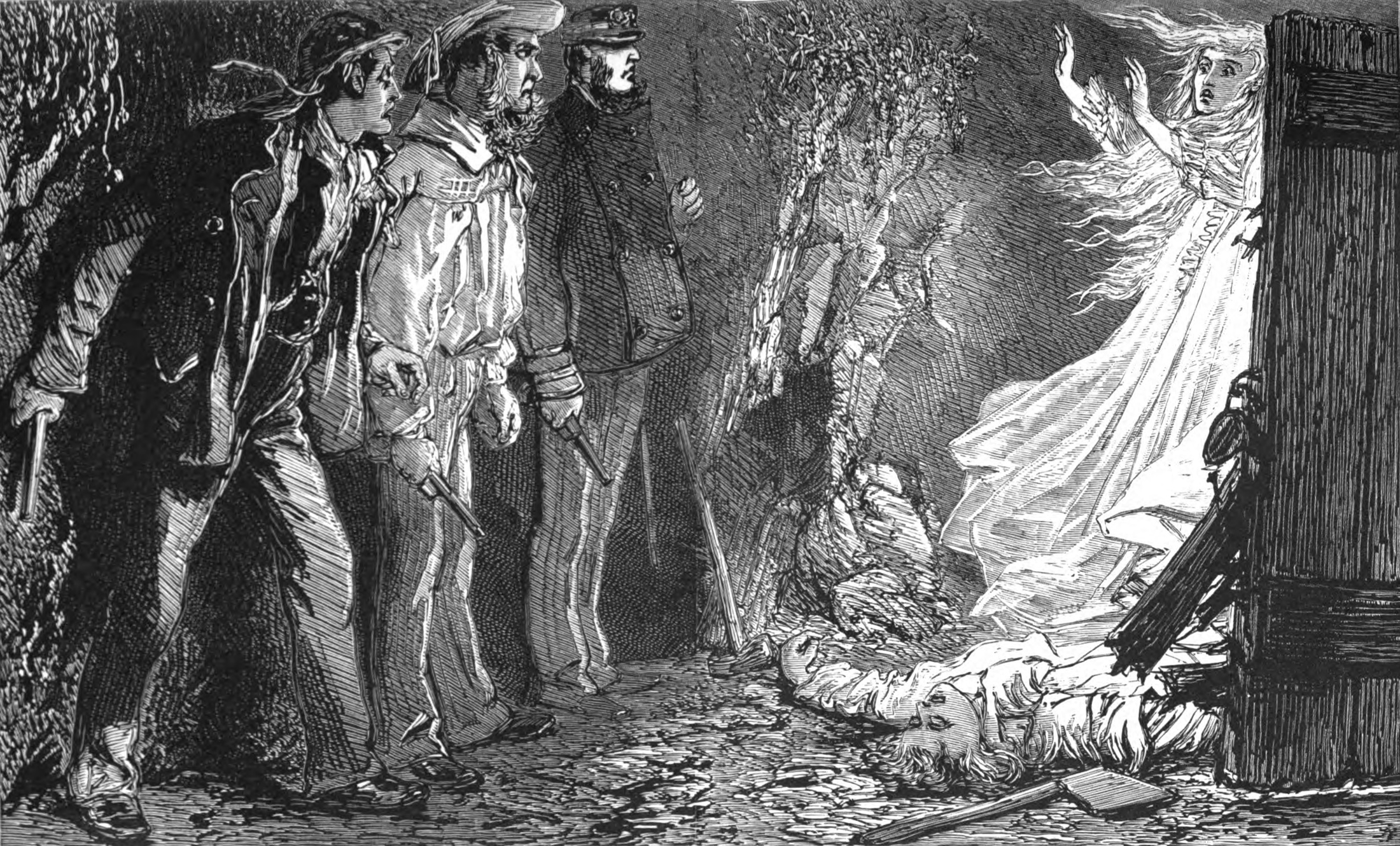

All at once the struggling and oaths commenced close to us in the cellar. The words were audible now—"Down, d—n you, down!" in harsh rough tones, intermingled with heavy blows and feeble moans for mercy.

Suddenly, before our very faces, the door which we had fastened so carefully flew open, and the step went by us as we crouched back almost into the very wall. The struggling now sounded up in the watch-room, and then again seemed coming nearer to us, step by step, as if a heavy body was being lifted down the stair. I glanced at my companions; they were both ashy pale, but seemed calm and resolute. The steps came nearer, nearer, and again passed into the cellar; and again the wild cry of "George, George! for God's sake don't murder me!" rang out close by; and as the words died away, a vision appeared before us, the horror of which, even at this lapse of time, makes me shut my eyes in dread. By the light of a pale lambent flame that seemed to spring from every part of the cellar, we saw the dead body of a man lying on the ground, the face and head so battered and covered with blood as to make the features undistinguishable. Over it stood a woman in her night-dress, her arms extended as if to ward off a blow, while from a gaping wound in her throat the blood poured down in torrents. I remember the agonised entreaty visible in the large blue eyes, and the rippling masses of golden hair contrasting strongly with the blood-covered bosom—but no more; for I fell insensible. When I came to, I found myself in bed, and so deplorably weak that I could barely turn round. I had been nearly dying, it afterwards turned out, from an attack of brain fever, brought on, the doctor said, by over-mental excitement.

It appeared, on after inquiry, that the vision scarcely lasted a moment after I became insensible; that Mr. Thomson and Wilson, who had retained their senses, although terribly alarmed, had carried me upstairs, when, finding that I only roused out of my insensibility to become delirious, I had been removed to the hospital, where I had remained ever since. Mr. Thomson was so much impressed by what he had witnessed, that he determined to have the lighthouse thoroughly searched; and next day, taking a large party and plenty of light, the cellar was closely investigated, and the hammer which lay in the corner found to be covered with blood and human hair. Close by the wall, and, as nearly as they could judge, below where the vision had appeared, a large stone had been apparently recently moved, and Mr. Thomson determined to take it up. This was done; and after removing a quantity of loose sand, the decomposing bodies of a man and woman were discovered exactly as they had appeared to us—the woman in her night-dress with her throat cut, and the man with the skull horribly fractured and the face beaten in.

The remains were identified as the wife of the late keeper, and the son of a neighbouring farmer, who used to be a good deal at the lighthouse. Information was at once given to the police of the discovery of the double murder, as no doubt it was, and a strict search was instituted after the late keeper. It was months before he was traced, and then only found almost on his deathbed.

Before he died, however, he confessed the crime with which he was charged, and even described how it was committed.

It appeared that he had long suspected his wife of too close an intimacy with a young man in the neighbourhood; and one Friday night, while on shore, received what, to his jealous mind, was a confirmation of his suspicions, and, frenzied with rage, determined to have revenge. The next night he contrived to get the young fellow off to the lighthouse; and after plying him with drink till he was almost insensible, he dragged him to the cellar, and dispatched him with repeated blows of a sledge-hammer.

Maddened with brandy, and now determined to complete his vengeance, he rushed upstairs and dragged his wife down from her bed; and showing her the mangled remains of her supposed lover, cut her throat, in spite of her entreaties and declarations of innocence.

Fearing lest the sea should reveal the crime, he buried the bodies in the cellar, and taking a few valuable articles to divert suspicion, fled the spot.

Even while in the throes of that death which defeated the ends of justice, he declared that by day and night his wife had haunted him, and that, from the hour in which he had done the deed, to the time he had confessed it, he had never known one moment's peace.

Philosophers may account for the scenes I have related, or learnedly disprove them, as they please; I only know that, from being an utter unbeliever in the supernatural, I have now got so much faith in it, that, though my present way of life is quite unconnected with the sea, I never hear the plash of the waves without recalling with a reminiscent shudder the hours I passed on the "Haunted Rock."

The above story is in the public domain and can be copied or distributed freely. Credit to this site appreciated, but not necessary.