PART I.

"COMING EVENTS CAST THEIR SHADOWS BEFORE."

CHAPTER I. FIRST IMPRESSIONS.

It was in the late autumn (October 1845) that I came to my new home at Overton. Our house was near the outskirts of the town; and I wondered, on arriving, that my husband, as doctor of the union, and having, as he had told me, an extensive practice in the neighbourhood, should have selected so lonely a spot for his dwelling-place. Overton was a second-rate town, with no particular manufacture, and an absence of life or movement, except on Friday, the only stirring day of the week, when the stock farmers of the neighbourhood congregated at the Bull Inn to discuss market prices and the weather; whilst the lowing of oxen, bleating of sheep, and grunt ing of pigs broke the silence of the usually dull and deserted market-place.

There was little to interest the eye or ear in Overton: ill-paved, ill-lighted, with shabby shops, and an air of decay about the houses and of languor about the inhabitants which could hardly fail to strike a stranger passing through the town, and, of course, made a deeper impression upon me, looking upon it as my home.

I had met my husband at a long distance from Overton, at a seaside watering-place, full of gaiety and life, where he had been spending his brief summer holidays; and we had been thrown together as people generally are in those places—meeting on the beach in the morning, riding on the downs in the afternoon, and dancing at the Assembly Rooms in the evening. In less than two months after our first acquaintance I had become Dr. Connor's wife.

I shall not mention any circumstances connected with my own family, as they are unimportant in their bearing upon my dark story. This only I shall state, that my marriage was looked on coldly by my nearest relations; and that a feeling of wounded pride led me to drop all correspondence with them, and to determine to rely for my sources of happiness on my husband and home.

Let me recall the evening of my arrival at Overton, after three happy weeks on the Continent. It was in the thickening of twilight of an October evening that my husband handed me out of the train at the Overton station; a man-servant was waiting for us on the platform, and at the first glimpse I was conscious of a feeling of dislike and depression, arising from the anxious look that he fixed upon me, and as I turned to avoid his gaze I found that my husband was also regarding me with a strange look of inquiry.

"You have not returned Simon's greeting," said he; "he is an old and trustworthy servant, and will do his best to please his young mistress."

The man gave a wintry smile, that only seemed to make his face more inscrutable, and turned away to collect my boxes, which were soon packed upon the jangling fly. Simon mounted the box by the driver, and we were jolted down the muddy road and over the rough streets of Overton. A sharp turn brought us into the market-place, now lighted by a few dim oil lamps. The creaking signs of the two inns kept up a dismal duet in the foggy evening air.

A larger and brighter lamp was burning before the only respect able and cheerful-looking house in the market-place. A smartly-painted door and six upper windows led me to think that this must be our house, and I turned to my husband to ask him if it was so.

"No," said he; our house is not exactly in Overton, but stands about half a mile off on the Ambledon-road; this is Lawyer Piggott's, one of our magnates in this small place."

The fly rattled on, leaving the better streets and coming into a region of squalid cottages, interrupted by spaces of ill-cultivated garden-ground.

Soon the cottages ceased altogether, and about a quarter of a mile farther we pulled up before a tall brick house, with iron railings on each side of it, and a flight of stone steps up to the door. The windows were dark, and no light of welcome brightened the aspect of this place. Simon got down and rang violently at the bell, and my husband looked annoyed at the tardiness of the woman, who at length opened it.

"Didn't you get my letter, Mrs. Judson?" he asked angrily, as we entered the passage.

"Yes, sir," said the woman, curtsying, and, as I thought, look ing at me narrowly from head to foot; "everything is ready for Mrs. Connor."

It seemed to me that she laid a particular emphasis on my name. She held a candle in her hand inviting me to follow her up-stairs, whilst my husband opened the door of a well-lighted parlour, in which I could see that the cloth was laid for dinner. I followed Mrs. Judson, and was agreeably surprised to find how much happier and brighter it was inside than I had been led to expect from the exterior.

There were two windows in the bedroom, and on raising the blind I found that they looked on the long garden at the back of the house.

"This is a back room, ma'am," said the woman, "but master ordered it to be prepared; and indeed at this time of the year it's far more pleasant than the front one, and I may say that nearly all the best living rooms look this way."

"It can't be a very large house," said I, as I began to take off my bonnet and cloak.

"Well, ma'am, 'tis larger than you'd think, I daresay; and though certainly 'tis lonely, 'tis also very convenient."

She spoke kindly, but did not relax her scrutiny; still I thought this natural, so taking a look round the room, recognising some engravings of pictures I had admired abroad, and nicely bound copies of most of my favourite poets, I ran down-stairs to thank my husband for these little proofs of his watchful love.

I looked for him in vain in the lighted parlour, and being impatient to tell him of my delight, I crossed the passage, and pushing open a door opposite the dining-room, found myself in what was evidently the dispensary. This, too, was empty, but a ray of light found its way through an imperfectly-closed door on the other side of the room; I gently opened it, and saw my husband standing with his back towards me, looking into the half-open drawer of an old-fashioned bureau, which appeared the only piece of furniture in the room. Within it I caught a glimpse of something white and gauzy, like a woman's veil. A strange thrill even then crept through me as I stood, not venturing to draw nearer, though my curiosity was at once aroused. It was a narrow closet-like room, with no fireplace; and seemed by its damp darkness to swallow up the rays of the candle which stood by my husband's side. He turned suddenly as my dress rustled against the door, closed the drawer hastily, and advanced towards me with an agitated and eager manner, uttering an exclamation of alarm; then with a rapid change:

"Why, Georgie, how did you find your way into this dark hole? Come, my love," said he kindly, back into life and warmth and light. "Doctor's wives are never allowed to penetrate into the mysteries of the dispensary amongst poisons and horrid instruments."

Did his voice tremble as he said poisons? or was it my imagination? It was not until we got back into the light and warmth again that I noticed how pale and wan my husband's face had become; and the evening passed and turned into night ere the troubled expression faded out of his dark melancholy eyes.

CHAPTER II. MRS. PIGGOTT.

The occupations of a young wife in settling down in a new home are always sufficient to employ her thoughts and time. I had therefore but little leisure at first to indulge in surmises or speculations on many points, which gradually began to raise questions and doubts within me: now and then indeed—even during the first week—after our return home I wondered whether my husband's position was sufficiently established to admit of my being treated as an equal by the squires' families amongst whom he visited as medical man.

No cards as yet graced the china basin on my writing-table. I had decorated the room, which I called my drawing-room, with the usual pride of a young married woman. The coloured Bohemian glass, the Sèvres inkstand, the French clock, and all the pretty appurtenances of a newly-furnished apartment, had been arranged and rearranged, but as yet no eyes had admired them but my own. My morning hours were spent in reading, playing over my husband's favourite songs, and settling my household affairs with Mrs. Judson. In the afternoon I paced the garden, for as yet I had not summoned up courage to face the town by myself. My husband generally left home at half-past nine, and I seldom saw him again until our dinner hour at six, though I frequently waited for him till seven. From this I judged that his practice must be extensive, and that he probably rested somewhere in the middle of the day, as I hardly deemed it possible for one horse to take him over so many miles without respite; but I had a certain kind of timidity which I thought becoming in the wife of a professional man, and therefore never asked him questions as to the houses he visited, but accepted any little scraps of talk which he vouchsafed as pure acts of grace on his part. Mingled with my strong admiration and love I had a curious feeling of hesitation in seeking any light on his past life and associations.

His conversation seldom turned upon every-day incidents, but was rather drawn from the many sources of information and original thought in his own richly-gifted mind. He frequently would read me papers of an essay-like kind which he had written on abstract subjects. The evenings were always full of pleasant intercourse, though we never seemed to enter that inner region of confidence which is the great blessedness of happy married life.

At length one solitary card appeared in my basket. I was sitting alone as usual about three o'clock in the afternoon, tired of my monotonous employments, and counting the hours till my husband's return, when a ring at the front door made me start nervously; it was the first time I had heard the bell of my own house since the night of my arrival. At this slight but unusual sound, a presentiment that it was the note of warning of evil to come rushed through my mind. I laid down my work, and looked towards the door in anxious expectation. I was disappointed, however, for Mrs. Judson's face alone appeared with a card in her hand, which she handed to me; it was black edged, with "Mrs. Piggott" inscribed upon it. I was too glad of an opportunity of exchanging a few sentences with Judson, who went through all her duties with perfect regularity and cleanliness, but more as if she was moved by clockwork than by the instincts of a human being.

"Is this the old lady," I asked, "whom I have seen at church in Lawyer Piggott's pew?"

"Yes, ma'am; it is the lawyer's mother. She's an excellent lady, and I am afraid she's overwalked herself coming this distance; it's an uncommon thing to see Mrs. Piggott so far from home."

"Then run after her, and beg her to come in and rest herself."

"I don't think it'll be of much use, ma'am," said Mrs. Judson; "and she's too far back by this time."

"Pray go!"I repeated. I cannot bear the thoughts of this old lady walking so far without resting. I must go myself," I said, rising, "if you dislike the trouble."

"It's not the trouble, ma'am," said she quietly; "I'll do as you tell me;" and immediately ran down the steps into the road.

I followed her, and stood at the door watching my first visitor with some curiosity. She had gone some paces, and was walking with the feeble gait of advanced years. She turned on hearing footsteps behind her, and showed a face of shrewd kindliness; her hair was very white, while her eyes were dark and bright, which gave her face a very penetrating and keen expression.

"My mistress hopes you'll walk in, Mrs. Piggott," said Judson; "she's sorry you should have walked so far."

"My compliments to your mistress," said the lawyer's mother—and her voice sounded very distinct in the wintry air—"but I should prefer receiving her at my own house, and I'm not at all too tired to walk home at once. Tell her, if you please, I am obliged to her for her politeness, and hope soon to see her."

As she finished speaking she caught my eye, and curtsied with the formality of the old school. I returned her greeting, and went back to the fireside meditating on this little incident. Why was it that I scrupled to tell my husband of this visit? I looked at the card, and debated whether I should leave it in the card-basket or put it in my writing-case. I had a sort of feeling that if my husband saw it he would forbid me to return the visit. He had already spoken of Lawyer Piggott in a disparaging sort of way, and had usually discouraged my going into Overton on any pretext, except to church on Sunday.

Five o'clock struck, and I went up-stairs to change my dress; before my toilet was over I heard my husband's voice in the passage. I instantly remembered I had left the card in the basket, and that he would see it without any preface from me. I listened, wondering whether he would ask Mrs. Judson for an explanation of it, and heard a whispered inquiry and answer in an equally low tone from her. I could not discover if it was a tone of vexation or approval; but I hastily finished dressing and ran down to my husband, deter mining to express to him the pleasure I felt at the thought of making an acquaintance at last.

He was looking thoughtfully at the card as I entered the room. "Have you seen Mrs. Piggott, my dear?" he asked at once.

"I can hardly call it seeing her, Robert, for she would not come in. I was very sorry that she refused my offer of rest and refreshment, though I sent Judson after her; it was so very kind of her to come so far to call on me, and I hope you'll let me return her visit. I like her face," I added, "and have always wished to know her since I saw her at church."

He still stood looking musingly at the card, and presently said, in a kind tone of voice,

"Poor child! It's natural you should wish for a friend, and I'd rather you had Mrs. Piggott for one than any one else about here."

"Thank you, Robert; and you'll come with me, won't you?"

His countenance fell.

"No, Georgie, I have no time for visits except those of duty. I have long ago ceased to pay calls, and my presence will not be expected by Mrs. Piggott; you will be more welcome alone."

He dropped the subject, and it seemed as if, notwithstanding his praise of the lady, there was a tacit understanding between us that enough had been said about her.

CHAPTER III. OVERTON CHURCHYARD.

It was on a Saturday that Mrs. Piggott had called, and I looked forward with pleasure to exchanging a greeting with her on Sunday, and was therefore proportionately disappointed when an obstinately rainy day seemed to shut out all hopes of reaching church. My husband made no difference in his prolonged absences on the Sundays; they were evidently no rest days to him; and I had hinted more than once how much I wished that he would manage to accompany me at least to one of the services.

Generally he would reply to any observation of this sort with a very tender expression, partaking almost of pity; would smooth my hair with his hand, and say, "Poor little woman! There are many ways of serving God without going to church. The duties of a medical man are not the least among them." With these kind of excuses my husband would silence me for the time; indeed, he had a peculiar art in turning from any subject on which we were likely to differ. Accordingly, on this particular Sunday I saw him depart soon after breakfast, and prepared to pass the morning as well as my now-constantly-recurring feelings of uneasiness would allow me.

After reading for a while, I rose and looked out of the window, and, to my great satisfaction, noticed that the clouds were breaking, the rain falling less heavily, and a struggling gleam in the distance led me to hope for a fine afternoon. I had an unaccount able desire to reach Overton Church that day, and long before I need have set out for the afternoon service, I had put on my waterproof and was splashing along the wet road. The streets of the town were more than ever repellent on that November afternoon. I scarcely met a human being as I passed along. A few lads were lounging against the iron railings of the churchyard, who stared at me as I came up to them, and as I passed into the porch one of them said to me, "Church doors a'n't open; bells a'n't begun yet." I thanked him, and walked round into the churchyard, which was one of the old-fashioned kind, crowded, neglected, ill-kept, and full of monuments of more than usual ugliness. One end seemed reserved for the poorer classes, as the graves were distinguished by no headstones. One there was, however, which I noticed had a plain flat stone let into the turf, and towards this I walked slowly, and read the words:

"AMY CONNOR, died December 17th, 1844."

This was all that was upon the stone! It must have been some near relative of my husband's, for I had heard of no other Connors in the neighbourhood. Why had he never mentioned to me her loss? Why never even named her to me? She could not have been dead a year when I came to Overton. Now again sprang up an earnest desire to see Mrs. Piggott, and learn from her something of my husband's former circumstances; everything as yet was so vague and shadowy in my own heart, that I dared not examine its growing doubts. I was but nineteen, and more inexperienced than women are nowadays at that age; had I been wiser and older I should have hesitated before I sought from a stranger the elucidation of my perplexity. While I stood still gazing at the stone, the bells began to chime, and stragglers to enter the churchyard.

I resolved to wait till I saw Mrs. Piggott, and then to follow and seat myself near her in church. She came at length, leaning on the arm of a tall gentlemanlike man, in whose face I could see enough of the mother reflected to be convinced that it was no other than her son, Lawyer Piggott, of whom I had already heard. His eyes seemed to take in in an instant every one in the churchyard; and I was conscious that his look rested on me for a moment with a surprised expression. Mrs. Piggott bowed to me, and he raised his hat, and they passed into the church. I followed up the aisle and entered the pew immediately behind them, which was fortunately tenantless. I fear I was far more occupied with the lawyer and his mother during service than with what was going on around me. My attention was suddenly diverted by the pelting of the rain against the windows, and the howling of the wind, which seemed momentarily to rise into greater violence. I noticed Mrs. Piggott lean towards her son and whisper something, to which he nodded gravely; and when the sermon was over, and we were preparing to leave the church, he came forward and said:

"My mother is anxious you should take shelter in our house, Mrs. Connor, until this storm is over."

I was too glad to accept the invitation. Here at once, I thought, is an opportunity of satisfying my curiosity. I refused the lawyer's proffered arm, and begged Mrs. Piggott to go on with her son, while I followed. The church stood in the market-place, so we had only to cross this to reach their house. The old lady took my hand as we entered the hall, and said:

"Welcome, Mrs. Connor; I have wished much to see you here."

A broad staircase led us up into a long and comfortable room, which looked half library, half drawing-room, and in which traces of the son's occupation were noticeable. Mrs. Piggott drew two arm chairs up to the fire, and turning to her son, said, with a smile:

"I daresay Mrs. Connor will excuse you, Archie; so if you will send us up some tea, I will try and keep her," turning kindly to me, "till the storm is over."

I was won by the kindness of the old lady, and seated myself by the fire, with a suppressed eagerness on finding myself embarked in what might prove a confidential conversation with Mrs. Piggott.

"I'm afraid, my dear, you must find it lonely?" she said in a motherly tone.

"Very lonely," I replied; "but I hope my husband will take me into the country when the weather is finer, for as yet I have seen nothing of the neighbourhood."

"Have you no visitors, then?"

"Not a single card has been left on me since I came, except yours."

Mrs. Piggott mused a little; then:

"Has not Dr. Connor taken you to Carwithen Castle, and introduced you to his great friend, Lord Carwithen?"

"No," I replied. "Is it near enough for a drive? I thought it was the other side of the county."

"It is but nine miles from your house, and your husband is frequently with him; no doubt you will soon know him. But you have an excellent companion in Dr. Connor; he is a man of such varied information."

"Yes," I said, with a half sigh; "but I am so much younger and inexperienced, that I am not the companion to him that I ought to be; but he's very, very kind."

"Well, I'm glad," said she, "that there's a lady at the Moor House once more."

I caught at the words "once more."

"Did you know," I asked, "the Amy Connor whose grave I saw for the first time this afternoon?"

Her kind face clouded over as she answered, "Yes. I knew her as much as any one could know a being so unfortunate."

"Why so unfortunate?" I said, my curiosity and anxiety increasing.

"My dear, is it possible you have never heard of your husband's only sister, and of her melancholy history?"

"Never!" I exclaimed. "I did not even know that he had a sister."

More than a minute passed before Mrs. Piggott spoke again, as if taking counsel with herself.

"I fear I have not been wise," she said at last, "in thus talking, as Dr. Connor has not mentioned the subject to you himself."

"O, I am sure he will tell me all about it," I cried; "but if it is a painful story, that has been reason enough for his concealing it from me. Pray tell me all, Mrs. Piggott."

We were interrupted by the entrance of the servant with tea, and the three cups showed that the lawyer meant to join us. I was sorry to think we were to be interrupted, for my anxiety was growing stronger every moment.

"I think I must ask Archie's advice," said the cautious old lady, and rising she suddenly left the room.

I began to ask myself, in her brief absence, whether I was right in seeking from a stranger's lips the information on a piece of family history which my husband had thought fit to withhold from me; but I felt the opportunity might not occur again, and I could not bear to return home unenlightened. Mr. Piggott came back with his mother in a few moments, and seating himself near me said, with a grave but kindly manner:

"My mother tells me, Mrs. Connor, that you have never heard any of the circumstances connected with your husband's sister. I do not think it would be right that I, a perfect stranger, should make so painful a communication to you. I feel it would be better for your peace of mind that you should at once seek for information from Dr. Connor, and not risk the first hearing of so sad a story from persons who might be less disposed to feel for you than we are."

I trembled as he spoke. An air of sternness had been apparent as he mentioned my husband's name; and I felt that I dared not make a farther inquiry. My heart beat with an indignant sense that this man blamed and distrusted my husband. I rose hastily, tied my cloak, and prepared to depart, feeling much more friendless than when I had entered the house. Mrs. Piggott stayed me.

"My dear young lady," she said, in a sweet and pitying tone, "Archie is right; only Dr. Connor's lips should tell you of the past. He has had some good reason, doubt not, for keeping it from you. Open your heart to him; he must need comfort more than you or we can tell. Let it be your mission to give it him. Be his consoler. A wife's tenderness is the best balm for such wounds as his. If he will allow us to be your friends, come to us again, and we will then, if he approves, tell you all that we know of the past sorrow; but it must only be by Dr. Connor's permission and express sanction."

She drew me towards her and kissed my cheek, which was burning with mingled feelings. Mr. Piggott attended me in stiff silence to the door, bowed formally, and allowed me to depart with out a single reassuring word. And so ended the visit I had longed for, and I took my way home through the wintry twilight with a sinking and heavy heart.

CHAPTER IV. A REVELATION.

My mind was lost in a sea of conjecture, as I sat by the fire awaiting my husband's return on that dim November evening. Questionings, doubts, and surmises were thronging on me into which I dared not examine. Why had my husband never spoken to me of his sister? Why had Mrs. Judson never alluded to or mentioned her death, which must have taken place in this very house only eleven months ago? I remembered, with a shudder, that start of horror when I surprised my husband in the little room beyond the dispensary on the first night of my arrival at Overton.

"Why," I asked myself, "did Robert never allude to the names of any friends or neighbours, or hint at my finding associates in the ladies of the neighbourhood? Where did he spend all the long winter afternoons? Surely he could not be always engaged in visiting the sick! Why did he never return to the house by the same road he left it? Why was the front room adjoining my own always kept locked, and never entered, to my knowledge, even by Mrs. Judson?"

As I pondered over these and many even darker suspicions, I felt a growing reluctance to ask him about the past, and yet a curiosity which I knew would impel me to make inquiries in some other direction. This mixed feeling deepened as the time drew nigh for his return, and I listened nervously for the swinging of the gate that opened on the common, by the sound of which I generally knew of his arrival. It had always been my habit to rise and welcome him in the passage—greeting him with a wife's kiss; but this evening I was chained to the chair, and sat still, trying to suppress my agitation and to appear calm and natural. I had forgotten, till he entered the room, that I still wore my bonnet and cloak, and that he would remark on this unusual disregard of my evening change of. dress.

"Little wife," he said as he came in, "have you forgotten that you have a husband to welcome?"

He came forward into the firelight as he spoke, and I rose to meet him.

"Why, your hair is quite damp," he said, as he smoothed my curls back from my face; "where have you been so late?"

I felt my colour rising as I answered, "I have been to church."

"Church!" he repeated, looking at the clock on the mantel piece, the hand of which pointed to a quarter to seven; "why, your service must have been a very long one, or you must have been very imprudent, sitting here till so late in your wet things!"

I was growing more and more uncomfortable. I hesitated, and then stammered out, "I returned Mrs. Piggott's visit after church."

Something in my manner made him look at me more narrowly.

"What is the matter, Georgie?" he said.

"Why, Robert, I think I must have caught cold; and this damp dark evening makes me feel quite wretched."

"This is the last time, then," he said, "that you must go to church in the afternoon during the winter."

Then, suddenly changing his tone to one of stern inquiry, "I have a perfect reliance on your truthfulness, and I require you to tell me on what subject Mrs. Piggott has been talking?"

I attempted to answer, but broke down, and began sobbing violently. He sat down and drew me gently towards him.

"Be calm, Georgie. Shall I guess what you have heard this evening?"

"Forgive me," I cried, "if I have done wrong. I have been tempted to ask questions about your poor little sister, but I have not heard anything but that you lost her, and that she was unfortunate. I am so very, very sorry for you, my Robert. Will you not let your little wife try and comfort you? Will you not confide in me?"

The clock ticked on; the room was very silent. I could feel my husband's heart beating as I stood up and put my arm into his. His voice sounded thick and husky when he next spoke.

"There are some sorrows so very dark that even love cannot lighten them. I am not angry with you, but you must tell me all. What led you to ask questions as to the past? I do not think Mrs. Piggott would have volunteered the information."

I shivered as I said, "I saw her name on a grave in the churchyard."

He struck his hand against his forehead as he murmured some indistinct words; then, relaxing his arm, he turned from me, bidding me go and change my dress; and as I reached the door he added, "I will try and let you know something of the miserable past, since you wish it; but it will be a heavy burden for your poor little heart. I would fain have kept it from you. You have drawn it on yourself, and I cannot help you to bear it; for—"

Here he broke off, laid his head down on his folded arms on the mantelpiece, and groaned heavily. I left the room in frightened silence, and tried, during the short interval till we met at dinner, to restore myself to my natural demeanour. The meal passed without any conversation between us. My husband was absorbed during the whole of the dinner, and seemed to pay attention to what was going on with difficulty. Simon stood behind his master, and looked as if he were keeping a silent watch on Robert. At length he left the room, and we were alone. My husband sat still at the table, leaning his head on his arm and shading his eyes from the lamp. At last, breaking the silence, which had grown oppressive, he said,

"Will you tell me, as briefly as possible, all that you have heard of my"—he stopped—"of Amy's death this evening?"

I trembled, but knowing how he disliked outward signs of nervous weakness, I repeated word for word Mrs. Piggott's replies to my questions. When I came to her leaving the room to seek her son, he held his breath and looked up fiercely. I went on, and with a faltering voice mentioned Mr. Piggott's refusal to tell me any particulars, and his injunction to ask my husband, and him only, for the history of his sister and her sorrowful end. He rose and began to pace the room with an impatient and angry air, his usual sign of annoyance or disquietude. I sat still, grieved and frightened; for though I was a mere girl, I quite understood how galling it must be to his pride for one of his own sex to have thus spoken of him to me. His face grew darker, more suspicious, more wretched. He continued to pace backwards and forwards, uttering expressions of dislike and contempt, which I felt must be levelled at the lawyer.

"Meddling hypocrite!" he said at last. "Couldn't he have left me this one comfort in my blighted life? How dared he speak thus to my wife!"

"Robert," I said, "he never blamed you; he only counselled me to ask for your confidence—"

He broke in: "I cannot discuss this subject to-night. Give me time to collect myself. I am too hurt and grieved to talk more to you now. I will consider in what way to tell you what you desire to know. This home will be darkened by the knowledge; but it is too late—let the cloud fall."

I went up to him and kissed his hand, but he was not softened; he withdrew it coldly and turned away. Most miserable did I feel as I went slowly up-stairs to my own room. I sat down by the window, lifted the blind, and gazed out. It was little more than a month since I had entered the house as a bride, and I felt as if my future life had suddenly changed and become dimmed by strange shapeless fears and forebodings. While I thus lingered Mrs. Judson came into the room. She was not in the habit of attending me at night, and I was surprised by her sudden entrance. I noticed an unusually sad and weary look upon her face, and that here eyes were red with crying.

She lowered her voice as she came up beside me, took my hand in both hers, and said pityingly, "Do not read this to-night, dear mistress; but I have no choice, and must give it to you. Dr. Connor has sent it up, and desires that when you have read it you will never speak of the subject again either to himself or to any one else. He sends you his love, but is too much distressed to see you again to-night." She placed on the table a large sealed envelope, and, with a look of sad meaning, said, "Good-night, and may you rest well; but do not, do not open this to-night. You are worn out. Pray for God's blessing, and go to your bed; you are over young for so much trouble."

The door closed on her pale warning face. I was stricken to my heart with a cold fear. What might this envelope contain? I was unable to restrain my hand a moment. I sprang to the table, tore it open, and saw a worn-looking country newspaper folded and refolded to suit the cover. Inside was written in my husband's hand, but in wavering characters, unlike his ordinary writing, "Read it, and burn it."

"Read what?" I asked myself, as I tremblingly unfolded it. Two black crosses in ink marked two separate articles. I sat down by the flickering fire; it was nearly out; the night was bitterly cold. A low sobbing wind wailed without in sympathy with my own sorrowful heart. I placed my candle on a table beside me, lifted up a supplication for strength to bear all I should read within it, and opened the paper.

The newspaper was dated Dec. 23, 1844. It was a copy of the Ambledon Courier, a weekly paper which my husband took in, and from which I had sometimes noticed that portions were carefully cut out before it was placed on my table. I read the shorter of the articles first. It was headed, "Melancholy Suicide of Miss Amy Connor, at the Moor House, Overton. On Friday night last, Dec. 17th, as Dr. Connor was returning from Ambledon about midnight he was met by his sister, Miss Connor, on the high-road between the turnpike and the second milestone from the town. The unhappy lady had only strength to stagger forward and fall on the step of the gig in which the doctor sat. He raised her, placed her beside him, and drove rapidly home. On arriving at his own door, about half a mile distant from the spot where he had met her, it was found that she had ceased to breathe. She was lifted out by her brother and by his two servants, Simon and Martha Judson, and placed on a couch in the sitting-room. Every means was used to restore animation, but it was apparent that the unfortunate young lady had died from the effect of a large dose of tincture of aconite, as a small phial, half emptied, was found tightly grasped in her right hand. The body awaits the inspection of the coroner and magistrates. Farther particulars will be given when the inquest has been held."

Years have passed since I read the dreadful words of this brief announcement, but they have remained stamped on the very substance of my brain. The longer article contained the particulars of the inquest. I cannot remember the sequence of the events, but I gathered that Archibald Piggott was the coroner; that my husband was the first witness called; that he led the way to the ordinary sitting-room (ah, heaven, our little home-room which I had so loved and rejoiced in!); that the body of his sister lay in rigid stillness, robed in a loose white robe on the couch; on her head a torn veil, with pieces of bramble entangled in it (that veil, had I not seen it when I interrupted my husband in the inner room?); in her right hand the fatal phial. The face was calm, the lips slightly parted and quite blue. I went on reading with strained and burning eyes. I seemed to see it all before me! My husband was asked many and searching questions. He was cross-examined by the coroner, and it was plain that dark suspicions were in Mr. Piggott's mind (which, perhaps, I shuddered to think were still there). But Dr. Connor's answers were perfectly satisfactory, and his deep grief and horror were most evident to all. He stated that Miss Connor had been insane for three years past; that he was her only natural guardian and protector; and that he had devoted himself to her, and placed with her, as her attendant, by night and day, an old and faithful servant, Martha Judson, who was passionately attached to the deceased. He said that his sister had never shown any suicidal impulses; that she was perfectly quiet, but invariably depressed, and, as is usual with the insane, could not bear to see himself, her nearest relative, as she associated him with one who had broken his faith to her, and whose ill-usage had led to her insanity.

On the night of the 17th he stated that he met her on the Ambledon-road, and saw at once she must have drunk the deadly drug at the moment when she saw the gig pass, as she expired even before he could raise her from the step. The quantity of aconite she had taken, he said, would cause death in sixty or eighty seconds. He had left the phial in Simon Judson's care, as it was to be carried to the infirmary early on the following morning. It had "Poison; for external use only," written on it in large letters.

Simon Judson was called. He confirmed the last statement, and said he had placed the bottle in his hat on a table in the hall, that he might remember his master's message about it in the morning. He had never seen it again until he saw it in Miss Connor's hand when he helped to lift her out of the gig.

Martha Judson was then summoned. She was in an agony of distress, and rushed forward to the sofa, throwing herself on the body, from which she could with difficulty be separated. She was hardly able to answer the questions which were strictly insisted on by the coroner, especially as to the time she left Miss Connor on the previous evening; but at length she gave the following evidence: That she had undressed the young lady, and that she had seen her safely in bed as usual, between nine and ten o'clock; that she had not noticed any excitement in her; that, on the contrary, she was more submissive than ordinary, and laid down more quickly than was her habit. The outer door of her room opened on the landing, and this was always locked at night. Mrs. Judson slept in the room with Miss Connor in a separate bed. She generally retired to rest herself at eleven, but on this night she had stayed talking to her husband till past midnight, when, as she was preparing to go up-stairs, she heard the gig stop, and ran out into the hall. As she did so she saw that the hall door was ajar. It flashed on her that Miss Connor must have stolen out, and she remembered with remorse that she had not locked the outer door of the bedroom when she had left her more than two hours before. In another moment she knew it was all over, and that her young mistress, as she called her, was dead. She sobbed out over and over, "And it was by my hand, for it was I who was her nurse, and who loved her, and yet I left her—I left her to wander out and die on the high-road."

The poor woman was removed from the room; and the verdict was returned: That Miss Connor had died from the effects of poison by aconite, taken under an access of insanity.

Dr. Connor was severely blamed for leaving so deadly a poison in a servant's hands under the roof with an insane person, without a strict injunction to keep it under lock and key; and a note was added by the editor stating that it was feared the above sad circumstances would lead to Dr. Connor's departure from Overton, as he had expressed himself as deeply offended by the manner in which the inquiry had been conducted.

Twice did I read this bald newspaper statement of the terrible tragedy which had been acted out under our miserable roof; then I rose, and tearing it into atoms set fire to them, and watched till every quivering spark was black and dead. I dared not think over the facts. My head was hot, my heart was throbbing, my thoughts were confused. I would pray—I would wait—I would be patient. Thus did I lie down alone, for the first time in my altered home.

CHAPTER V. THE SUMMONS.

The slow hours dragged on heavily. Under the happiest circumstances the closing days of November are generally marked by outward gloom. What these days were to me under the conflict of feeling through which I was passing can never be described. It was a bitter trial that, fight with them as I would, I could not keep down the rising doubts of my husband's truth and honour. Fain would I have trusted him as before, and each day when he was absent from me I endeavoured to school myself into the old confidence I used to feel; but with the return of the evening, as the shadows fell upon the landscape, even so fell the shadow of a great doubt across my own soul. It was with an effort now that I met him with a smiling face, and I soon saw that he knew it was such. The conversations we used to hold together grew more constrained each day, and at length he would take his reading-lamp and book directly after dinner and leave me to myself. Every day I determined that I would speak and break this spell of cold silence, and every day found me with a more fearful and sinking heart. And thus November closed, and the shortening days and wintry skies seemed to sympathise with the deepening obscurity over my own life.

One afternoon I determined to explore the moor by which my husband always returned home. I had usually confined my walks to the high-road between our house and Overton, instinctively shrinking from the barren bleak tract that bounded the garden. Pushing open the gate at the end of the gravel-walk I found myself at once upon the moor. A few cold white clouds hung in the gray sky; the ground was covered with a coarse marshy grass, and here and there stunted gorse and blackberry bushes heightened rather than relieved its desolate appearance. There was a track of wheels across it, but no actual road, and I judged that this must be the mark of my husband's gig, and that I should be right in keeping to it. I walked musingly on, and soon found that the moor was larger in extent than I had thought; for I must have gone at least two miles before I reached the Ambledon-road, which crossed it. The short day did not allow of my going farther, and I began to retrace my steps by the high-road, expecting it to be a more cheerful though perhaps a longer way home; but to my surprise I found myself at my own door in less than half the time I had taken to walk over the moor. I understood now why my husband chose the moor road by night, though it was the longest and roughest, rather than pass the spot haunted by so fatal a memory. Pity took possession of me as I thought what his state of mind must be, and I resolved to throw off the kind of nightmare fancies with which I was tormented, and try to be again the sunshine of his home. I ran up-stairs, and put on a white dress with bright ribbons, took pains with my hair, endeavouring to look like the happy wife he used to praise and admire. I made the room as cheerful as possible, piling on wood and lighting the lamp, and then stationed myself by the window to watch for his coming.

The gate was soon swung back, and I saw his tall figure coming up the path. Simon always met him at the gate to take the horse and gig to the stable, while he entered the house through the garden. I ran out to welcome him joyfully. He scarcely answered, but I saw by his face that he was pleased. I took studious care in no way to revert to the estrangement that had lately come between us, and though I could see how surprised he was at my manner, I knew he was gladdened by it; and when dinner was over, to my delight he remained in the room, and, seating himself by me, took my hand and said,

"Now, Georgie, have you anything you would like to ask me?"

I felt that I blushed, but I could not reply, as I knew that there was a host of questions I longed to put to him. He did not give me time to speak, but continued:

"Do not think, child" (I knew he had forgiven me by that kind word), "that I have not read very clearly what has been in your heart during the last fortnight. You have been struggling with many unworthy thoughts of your husband, but to-night you are more like your old self, and if it will please you I will tell you something of my earlier life."

I murmured that I did not wish him to do this if it pained him, though all the while I was longing to hear his story.

"Don't flatter yourself that you mean me to take you at your word," he said; "no, I will tell you a part of my story that will at least prove the confidence I have in your generous nature. How old are you, child?"

"Why, Robert, you know, only nineteen."

"And I am thirty-five, and from that fact you may guess at once that you are not the only one I have loved."

My foolish heart beat wildly as he said this, and with an impulse I could not resist, I cried,

"Is she alive now?"

"No, she died more than a year before I saw your face; and shall I tell you why I loved it? It was because it wore the same innocent yet proud dignity that rested on the face of my dead love."

"May I know her name?" He remained silent several moments, and then said,

"Yes; it shall not be a half confidence; you shall know it presently. I was not always a doctor;" he said this with a sort of ironical contempt; "ten years ago you would not have believed that the gay Captain Connor of the 30th could have become the grave sallow man who sits beside you."

"Were you really in the army, Robert? why did you leave it?"

"That involves a long story, but you must have it, I suppose; it will not give you a higher opinion of your husband."

He went on with frequent hesitation and evident effort, as if choosing his words and weighing their force and meaning.

"Well, I was extravagant and rash. I had talents, and might have made my father happy. He was a physician, and was most desirous I should study medicine, and follow the same profession. As long as he lived I obeyed him; but my wilful spirit never bent itself in earnest to my duty. I had no mother, she had died long years before; and when my father's sudden death released me, as I deemed, from the observance of his wishes, I found myself in possession of an ample fortune, and at once entered a fashionable regiment. Here, probably, I should have made shipwreck of character and fortune, had it not been for the major of the regiment, who became my best friend, and under whose influence I ought to have grown into a worthier man. But he left about two years after I had joined, and I only saw him at intervals, when I spent my long leave at his castle."

My husband stopped for a moment as if to consider; then:

"I may as well tell you that this man is Lord Carwithen, and the friendship I have spoken of is as strong as ever. Some day you shall know him, and you will learn to regard him as I do. On my second visit to his old home, I found his sister, who had been educated abroad, had come back to take her place as mistress of the castle. Carwithen and Lady Olive Mayne were orphans, and they seemed to live for each other. This girl might have been your sister; she had your hair, your voice, and tender beseeching eyes. At the close of my stay, my friend asked me to apply for a longer leave. He wished me to know his sister better, he said. Too gladly I remained; too absorbed I soon became in a deeper sentiment than I had yet felt for woman. It was winter, and after returning from shooting, I used to find her in the drawing-room by the fire-light. She had a voice that bound me with a magical spell to her side—tender and exquisitely musical; and soon we began to talk of graver themes than are usually discussed between officers and young ladies. She was one of those who ennoble one's nature the nearer one draws to them. I began to be ashamed of my worthless life; and when I left and looked back at the old Norman pile, which seemed to frown on my hopeless love and stamp the distance between its owners and myself, I vowed I would never return, but break off at once and for ever from the strong temptation of her presence. I had neither ancestry nor position. My extravagant habits had nearly exhausted my fortune, and I knew I should soon be reduced to a captain's pay. How could such as I lift my eyes to Lady Olive? A year went by. My friend and his sister went to Germany, and we ceased to correspond. Suddenly I met him in the autumn of the following year. He treated me with unchanged cordiality, gave me a hearty invitation to spend Christmas at Carwithen, and accused me of cutting him and treating him with unkind neglect. I refused the invitation, and spoke coldly and repellingly. 'Connor,' he said, 'I insist on knowing what you mean by this caprice!' I evaded his question for some time; but at last he drew the truth from me. Instead of treating my presumption with disdain, he wrung my hand warmly and said, 'Connor, my best wishes would be fulfilled if I could see you Olive's husband.'

"I was breathless with astonishment; but can you blame me that I yielded and went down to the castle with him? It was in the last days of October that I saw her again; she was gentler and more beautiful than ever; graver too, and showing more decided dislike of entering society. She went through all her duties as hostess with exquisite grace; but there was a languor and sadness at the end of every dinner or gay meeting which showed how great a burden she felt. it. The days went on, and I dreaded, yet longed, to tell her all. At length, urged by her brother, feeling the strongest doubt as to the issue, and knowing I was risking the happiness of my life on one cast, I spoke. I was met by the most decided, even peremptory, refusal. Unlike her usual self, she answered me with sternness, and let me know that her rejection was irrevocable. I did not wait to see Carwithen, but wrote a note, telling him of the ruin of my hopes, bidding him farewell, and praying him never to seek me again; and then left the castle, as I thought for ever, an embittered and almost desperate man. I took the step I had long contemplated, and sold out. I plunged at once into an obscure part of East London, returned to the pursuits of my youth, entered myself as a student again at Guy's Hospital, and strove in every way to cut off all ties with those who had known me in my military life. Seven weary years of disappointment and poverty passed by—years of misery; let them be blotted out!

He stopped, and almost groaned. I asked faintly,

"Was it then you took your sister to live with you?"

He moved his head in assent, and seemed struggling with some strange feeling. Presently he went on:

"I could not have given her a home before. Martha Judson had been her nurse and servant, and when my father died, she continued to live with her and take care of her. I cannot speak of this; remember our compact. I have more to tell you of Olive—shall. I go on?

I kissed his burning forehead, for my unfortunate question had brought back a wild look in his eyes, half suspicious, half remorseful; and I reproached myself for my persistency in reviving the forbidden subject. He pressed me to him, and at length went on, as if repeating a lesson:

"One wretched night, when I was returning from a more civilised part of the town than I was used to frequent, a friendly grasp was placed on my arm, and a voice rang in my ear with an old familiar charm: 'Connor, my dearest old fellow, where have you buried yourself so long? Come back to your old friends; we have tried to find you, and have felt that you treated us very ill, but we'll forgive you.' I stammered out that it was impossible; my circumstances were changed. I was no longer a fit associate for him. He interrupted me: 'No change of circumstances, no loss, except of honour, ought to shut you out from those who love you.' 'Love me!' I said bitterly. 'You forget, my lord, the reason of my hasty flight from your house seven years ago; and yet I think I wrote plainly enough.' 'That is a mystery,' he said, 'which only one person can clear up; you had better, nay you must, come and ask her yourself.' Again I repeated, 'It is impossible; you don't know what I am. I am a poor doctor, seeking for his daily bread by hard work.' Still he persisted, though he looked astonished, and drew me on in the direction he was walking. 'Listen to me,' he said; 'you know my unconventional ways—my Bohemianisms, if you like. I was never led by worldly maxims, and if that be madness, I am madder than ever. I desire nothing but happiness for Olive, and the poor child hasn't known what that means since you left us. You have been rash and wilful, Connor, and have shown little knowledge of woman's nature thus to accept the first rebuff; but you were always too proud and sensitive. However, I insist on your seeing Olive again; she is too noble not to explain her own feelings if you seek to know them.' I felt as if I were walking on in a dream. Could it be? Was I indeed to see her and hear the melody of her voice again? The fascination was too strong, and without at tempting farther resistance, I went home with my old friend. He took me into his library and begged me to compose myself. He entreated me, if I loved him as of old, to give him my entire confidence."

My husband paused, and seemed to gasp for breath.

"His goodness was too much for my almost-broken heart; it had been so long since I had heard a friend's voice or grasped a true hand. He listened to my brief and miserable story, of my hopelessness of taking a higher place in my profession, as I had no money, no patron, and little practice, even among tradespeople. I wound up by asking fiercely, 'And can you dream, my lord, of presenting an utterly ruined hopeless man to your sister? Let me go back to my obscurity, and forget, for heaven's sake, that you have ever known me, or think of me as the lost friend of your youth, for I am worse than dead to you and yours.' Lord Carwithen heard me patiently as I raved on in this bitter manner, but did not change his purpose. I cannot tell you all his persuasions and arguments. At length, finding they had no effect upon me, and that I was impatient to go, he cried out with strange anguish, 'Connor! Olive has not long to live! I have consulted physicians at home and abroad in vain. I have taken her to Madeira, to Egypt—every change, every means have been tried, but all is useless. My sister, my only be loved one, my guardian angel, is slowly dying of a cureless malady, for which, Connor, there is no name in science, for it is disappointed love.' I stared wildly at him. 'It is true,' he cried. 'It is too late; her life hangs on the slenderest thread, and yet though it is too late to save her, you, and you only, Connor, could help to make the few weeks she has left on earth happy!' Do you think I could have torn myself away after this? What was I, wretched and unworthy, that I should thus have been honoured by the love of so pure a being? I saw her again; my love became worship; and at last I learned, all too late, from her own gentle lips, the true reason of her rejection. A disease of the heart, which she had inherited from her mother, and which that mother had enjoined her to keep secret, had made her resolve to live unmarried, fearing she might transmit an hereditary curse to innocent offspring. Olive begged me still to keep this secret from her brother. She feared, poor child, that he might also think his own a doomed life, and might be led, as she had been, to pass it in cheerless celibacy, and leave no children to inherit his name. I did not dare to tell her that she had been the victim of a misguided judgment; and that under other circumstances she might have baffled the insidious disease, and been a happy wife and mother. I could not add to her sorrow by showing her that her sacrifice had been useless; but there was yet one blessing left me—one drop of consolation in the bitter cup which was my portion. My own researches in science had been directed peculiarly towards the palliation of heart complaint; and though hers was now of a hopeless character, I was enabled to alleviate her sufferings, and sustain the frame that was sinking, surely but slowly, into an early grave. I kept her sad secret from my friend; and when he found his Olive for a time wonderfully restored, that she could once more sing to him and join him in his drives, he could not believe that death was approaching, and reiterated his desire that I should become her husband. It was with difficulty that I persuaded him to dismiss this dream. And it was only by accepting the office of domestic physician, and taking up my abode under his roof, that I could entirely turn him from the idea. It would have been profanation to act on it. She was sealed for heaven, and day by day her beauty grew more spiritual and her mind more heavenly. We came down together to the old home for which she sighed, and there Olive's sweet life gradually ebbed out; and when the autumn leaves were falling she died, and was laid in the vault under the private chapel of the castle."

He stopped abruptly, and covered his face with his hands. Why was it that, as his mournful story ended, I thought with a quick dart of pain of the obscure grave in Overton churchyard? Sad as Lady Olive's fate had been, what was it but peace and rest compared to the tragic end of Amy Connor? Even at this instant, when my heart ached with sympathy, I knew and felt that he was hiding some lower depth of woe and shame in his past life; but I struggled against this conviction and threw myself on my husband's breast, while I told him, weeping, that I would give my life and heart to soothe and comfort him. I reproached myself for past coldness, and implored his forgiveness. He returned my embrace warmly, and told me that better days were coming. "Only love and trust me," he said, "and all shall be well. Carwithen has begged me to leave this place, and, treating me as he ever has, with a brother's confidence, has settled that we shall go to Nice with him after Christmas, and has persuaded me to arrange with a successor and give up my practice to him at once. Ever since you pressed me to tell you my sorrows, I have been striving to take you out of this woful house; but your coldness chilled me and kept me silent. It is over now. Let us look forward to a bright future in a new land."

We sat late that evening by our fireside. Never had I been so happy; never had I seen my husband so brilliant and fascinating. He gave me sketches of his adventures among the London poor, humorous and pathetic, and I sat with eyes riveted on his face as it reflected a hundred varying feelings, touched with tenderness or glowing with indignation, as he dilated on the wrongs and sufferings of the neglected dwellers in the cellars and garrets of East London.

That winter night was not to close without a singular change in the impression which it stamped on my memory for ever. How long I had slept I know not. It had been a happy dreamless sleep; I had not known so calm a one for many troubled nights. Suddenly I awoke; in one instant I was perfectly and vividly awake; a woman's voice with a wailing accent had uttered the name of "Robert Connor." It seemed to be close to the bed, close to my husband's ear, as he lay with head thrown back on the pillow, and the nightlight casting wavering shadows on his face. My heart beat as if it would break, and as I sat up and tried to quiet my excited nerves, I became conscious of a chill, damp and heavy as the dews of the grave, which struck to my very heart and made my teeth chatter. The fire was still burning, and there was no evident reason for this death-like cold; but it was no fancy, for turning shudderingly to awaken my husband, I saw with terror that he too was trembling, and that a cold sweat was breaking out on his brow. His features were convulsed, and with half-parted lips he seemed intently listening, his eyes but half-closed, and I saw that he was bound by some vision of the night. With an awe I could not conquer I listened for his utterance. He raised his hand twice, as if to keep back some figure from his side; his agony seemed to gather strength; he struggled to speak, and at last, raising his head from the pillow, he said, in tones so thick with horror that I could scarcely have believed them to be his:

"Amy, I will be there; the letter shall be given. I will be there, I will be there!"

Three times in choking accents and at a few moments' interval he reiterated the promise; and then, with a long-drawn groan of misery, he sank back, and his face assumed the profound quiet of one but newly dead.

I was filled with superstitious fear; but I could not speak. I had learnt some farther revelation of the buried secret—that sleep and night could not hide this woe and guilt, for guilt and woe they must be to force out this cry from his soul. I tried to pray for him and for myself; but a weight was on my brain, and no thought of heaven came, nor any idea but one—that Amy Connor's spirit had been near us in that room, and had summoned her brother to meet her. When would that dread meeting be? As I tried to quiet my still shuddering frame and lie down again, the church clock of Overton tolled one. I remembered that in another week the anniversary of Amy's death would come round, and I knew that the crisis of my fate was drawing near. O, night of unspeakable horror! How the long hours passed I know not. I dared not meet Robert's eye when the morning came, so pleaded headache, and begged that the room might be darkened, and that I might be left alone. I heard the door close behind him; then yielding to the suppressed feeling with which I had fought all night, I sank back in an hysteric agony of tears.

PART II.

"A SPIRIT PASSED BEFORE MY FACE: THE HAIR OF MY FLESH STOOD UP."

CHAPTER I. DEEPENING SHADOWS.

As I draw near the crisis of my history I feel a growing repugnance to trace the opposing feelings which struggled for mastery within me. I shall confine myself to the facts, as they stand out clearly and for ever in my memory. The voice which I had heard, and which was no dream utterance, had come to me at midnight on Friday the 10th of December, and I knew with a certainty no human reasoning could have shaken that the spirit of Amy Connor and my husband were destined to meet again on the anniversary and at the hour of her death. Robert remained from home till late on the succeeding day, and I was thankful to be alone; for strange to say, I had a deeper consciousness of a spiritual presence when he was within the house than during his absence. From the moment that I heard those accents of doom I was sure that there was an inevitable woe hanging over my husband's head. No human love or care could avert it, and I almost feared even to pray for him while he remained so obstinately silent as to this dark secret.

On his return home, then, it did not either surprise or pain me that he withdrew into the inner room, which had now become, in my mind, connected with the chain of circumstances leading on to the supreme event. But it was unusual, however, that he should order his dinner to be served alone; and Simon's gloomy face, as he told me of this arrangement, reminded me once more that this man too evidently knew much that had been studiously kept back from me. Deep silence seemed to reign over the house that night, unbroken and ominous; and I would have gladly escaped retiring to rest had it been possible, so much did I dread the solitude of my own room. As it grew later my nerves were more and more excited, and I started as the ashes fell from the fire or the branches of the rose-tree tapped against the window. It was nearly twelve o'clock when there came a rap at the door. I said, "Come in," in a hesitating voice, and Mrs. Judson's pale face presented itself.

"I hope, ma'am, you are not going to sit up and wait for master; when once he begins to write late at night I know he'll forget all about the hour; and you look ill and tired, and really, ma'am, you must take more care of yourself."

I felt grateful to her, for there was a feeling of security in her presence, and, indeed, I had always noticed from the very first a look of kindly interest in her eyes. I rose up, closed my book, of which I had read but little, and went up-stairs to my room.

The woman closed the door after me carefully, and listened for a few seconds before she came up to the fire, near to which I had seated myself. All was silent, and as if reassured, she said,

"Has master told you that he shall be leaving Overton very soon?"

I said yes, and that I was very thankful for it.

"This house," she continued, "is not a fit place for a young wife, and I've seen you growing weaker and thinner every day, ma'am, and have felt for you; for no one can bear such loneliness without losing heart and spirit; and I wonder how I've managed to stand it like I have, though I have seen more of the troubles of this world than you have, and have no reason to look for any happiness now."

Her tone was bitter, but still there was a good deal of pity in her look, and it encouraged me to say,

"I wish you'd tell me more about Miss Connor."

The change I had noticed before when Amy Connor was mentioned again passed over her face.

"Not to-night," she said. "If I ever talk to you about her, it must be in the daytime when the sun is shining. I couldn't bear it at night, and so near her room too." Then bending over me she said in a whisper, "D'ye know that she must have hidden herself in this room on the night she killed herself?" I shuddered, and rose up with the wild intention of seeking Robert, and asking him to take me at once out of this haunted and miserable house; but Mrs. Judson laid her hand on my shoulder, and said, "Don't betray me, ma'am. You don't know what you might draw down on your head if you speak to Doctor Connor; and you have no cause for fear, ma'am; there are always angels round the innocent. You can lie down in peace; and if you feel afraid of being alone, I will sit by you quietly till Doctor Connor comes up; but I mustn't talk to you, ma'am—'tis bad for us both."

She turned away, and began to arrange the things on the dressing-table.

I went to bed with the somewhat childish idea of keeping her with me till the hour of one had passed, and accordingly lengthened out my preparations for the night as much as possible. As soon as I retired to bed Mrs. Judson took a book, and sat still as a statue, reading to herself. Tired of gazing at her, my eyelids involuntarily closed, and I fell asleep before the church clock had struck the first hour of morning. I do not know how long this first sleep lasted; but when I woke the room was perfectly dark. I extended my hand, and felt that the bed was still vacant. I struck a light hastily, and found to my surprise that it was five o'clock. Glad that morning was approaching, and with a relieved feeling that I had been left alone—for, as I have said before, I was more conscious of a mysterious dread when he was with me—I turned on my pillow and fell asleep again. This sort of day and night was repeated up to Thursday; I only saw my husband at intervals, and then but for a few minutes. His look was increasingly wild, and though his manner was quiet and his words tender and considerate, he was evidently under the pressure of strong mental agitation. Whenever he spoke to me, it was as if he had to call his thoughts from some subject that engrossed them, and at times I could see his lips move, though no words proceeded from his mouth. I made several attempts to remonstrate with him, and to conjure him to let me be with him and comfort him. On that Thursday when he returned home he came into the room, and throwing off his greatcoat, laid himself down on the sofa, asking me to sit by him.

"Put your hand on my head, and cool it if you can; for I am sick, sad, and tired."

My heart yearned to him as of old, and all my love welled up again.

"O, Robert," I cried, "I would die to comfort you!"

He repeated the word "comfort" slowly to himself, and lay with musing eye gazing at the fire.

To any one who had entered the room it would have presented a scene of home-like happiness. I see him now with those sad expressive eyes, and with the lines of sorrow prematurely marked upon his forehead. What was I, ignorant girl, that I should presume to judge my husband? I am very thankful now that that evening was one of quiet peace and love. If he had deep forebodings, they were hidden from me. He had the manner of one about to embark on a long voyage, and who studies to keep back all mention of his approaching separation to save the grief of hearts he loves.

That night he slept by my side—a deep untroubled slumber. I passed the greater part of the night waking and praying, and the gray morning of the 17th December broke upon the monotonous round of our life with no added presage of the coming tempest.

CHAPTER II. AMY'S ROOM.

I wondered a good deal if my husband would leave the house on this 17th of December—this melancholy day!—and I tried in many ways to engage his attention after breakfast; and at length, when I saw him get up and prepare to go out, I asked him plainly to stay with me throughout the day.

It is impossible," he said. "I have an engagement I could not break. I must see Carwithen; so do not be frightened if I am not back till late to-night."

As he spoke the gig came to the door, and to my surprise I saw Simon seated in it, evidently about to accompany Robert. This was the only instance on which I had seen him go out, his usual employment being in the garden; and I had always felt glad that my husband seldom held any communication with this man. I went with Robert to the door, and stood on the step, giving him his driving-gloves. He usually made a point of avoiding all outward signs of affection before the servants; but to-day, as he was turning to step into the gig, a sudden thought or impulse seemed to strike him; and as I was still standing at the hall-door, he came back and pressed me warmly to him, saying in a thick voice:

"God will take care of you, Georgie!"

Before I had time to answer him he had jumped in and driven rapidly away.

I went back into the house, and paced restlessly about the room, unable to calm myself. I went up-stairs to put my walking-things on, determined to try and walk off my uneasiness. Hardly forming any definite purpose, I found myself in the streets of Overton. There had been an early service, and the people were coming out of church. I walked into the churchyard, and straight up to the grave whose tenant had now become the great object of all my doubts and fears. Yes, I had not been mistaken in the date on the tombstone; it was this day of the month, the 17th of December 1844. I stood at once enthralled by the multitude of conjectures that came rushing into my mind; and should have remained there, no doubt, much longer if I had not been aroused to visible things by a strange voice saying:

"Mrs. Connor, they are going to lock the churchyard-gate."

I turned, surprised at being addressed by name, and recognised the curate of the church. I followed him quietly as he left the churchyard, and as he locked the gates after us he looked up at the leaden sky, which was low and heavy.

"We shall have a stormy night," he said.

I felt a mocking bitterness at my heart, thinking how little this man knew of my anticipations of all connected with this night of which he spoke so quietly. He was a plain middle-aged man, and I felt no hesitation in accepting his proffered arm. We crossed the market-place in silence, but he said, as we were passing Mrs. Piggott's door:

"There is some one looking out for you at that window."

I looked up and saw Mrs. Piggott's kind face, warm with smiles of welcome, while she kissed her hand to me, and beckoned me to come in; but I shook my head, though I returned her greeting with equal warmth. It was the first ray of human comfort that had reached me for many a day. As I raised my veil to look up at the kind old lady, I noticed the clergyman give a half exclamation of surprise; it was explained soon after, and I took no heed of it at the time. The long street that led from the market-place was ill-paved; and as I walked along I became conscious how really weak I was, and once or twice almost tottered. Mr. Lambert begged me to lean upon his arm, adding:

"I have a daughter nearly as old as you are, Mrs. Connor, and you need not hesitate."

I thanked him, for any sympathy now was very precious to me; and I walked very slowly on, desiring to put off as long as possible the return to the shadow of that wretched home. Mr. Lambert began to speak of Mrs. Piggott, of her goodness and readiness to relieve and pity all who suffered.

"You cannot have a safer or a better friend," he said. "I wish we saw you more frequently in Overton; if you will honour me by calling on my daughter—for I have no wife living—she will be most happy to offer you any attentions in her power; but she is too young to pay visits herself."

From this he diverged to remarks on the neighbourhood and certain places worthy of a visit.

"Of course you have seen Carwithen Castle?" he said.

"No," I answered reluctantly.

"Is it possible? Why, Dr. Connor is the most intimate friend that Lord Carwithen has, and it is but nine miles from your door."

I said I knew this, and, with jealous fear lest any doubt of my husband's kindness should occur to Mr. Lambert, added: "My husband is too much occupied to take me out driving at present, but I hope ere long to see the castle, and become acquainted with Lord Carwithen."

"I should have thought you were not only acquainted but related to him," he said. "I had no idea, till you raised your veil just now, how like you are to poor Lady Olive Mayne, who died a year and a half ago."

"I have been told of the likeness," I replied. "Did you know her?"

"Yes; she often referred to me, desiring to know all cases of distress in Overton, and her purse and influence were ever at my command. She was a very angelic being, and her brother has never recovered her loss."

I thought of another brother and sister whose history was a dismal parallel to this noble and excellent one. Although I have said I would not speak of my own feelings during this terrible time, I must note here that two separate natures seemed within me during these few days. The struggle between good and evil that goes on in all human beings is not what I mean; with me it was another contest between my reasoning powers and wild impulses, amounting almost to madness, which prompted me to ask questions of the merest stranger, and to throw myself on the mercy and pity of any one who would listen to me. I had to struggle hard against this feeling now, for I knew the real fear that had haunted me through out these weeks since Lawyer Piggott's first disclosure was the awful thought that Amy Connor had not died by her own hand. And since the night of that spirit warning that fear had deepened into almost certainty, heightened by the horrible thought that I knew the author. I conquered the impulse, but Mr. Lambert went on:

"May I, as a father, give you a little advice? I cannot help thinking that you are nourishing and dwelling on many sorrowful thoughts. Pray make a vigorous effort to be cheerful; avoid lonely musings, which can lead to no happy result; come among your neighbours at Overton. Mrs. Piggott's and my own house will be always open to you; and assure Dr. Connor that it is my earnest wish to cultivate friendly relations with him. I cannot bear that he should live in this isolated manner, and his very uncommon talents should not be suffered to go to rust when they might be so useful to his fellow-creatures."

O, how my heart bled as I heard these words, and felt that happiness might have been attainable, but that now it was too late!

I could only thank him, and promise to give his message to my husband; and now we were close to my door; he shook my hand kindly and said:

"Do not let it be long before we meet again, Mrs. Connor; I shall come and find you out, if I do not soon see you under my own roof."

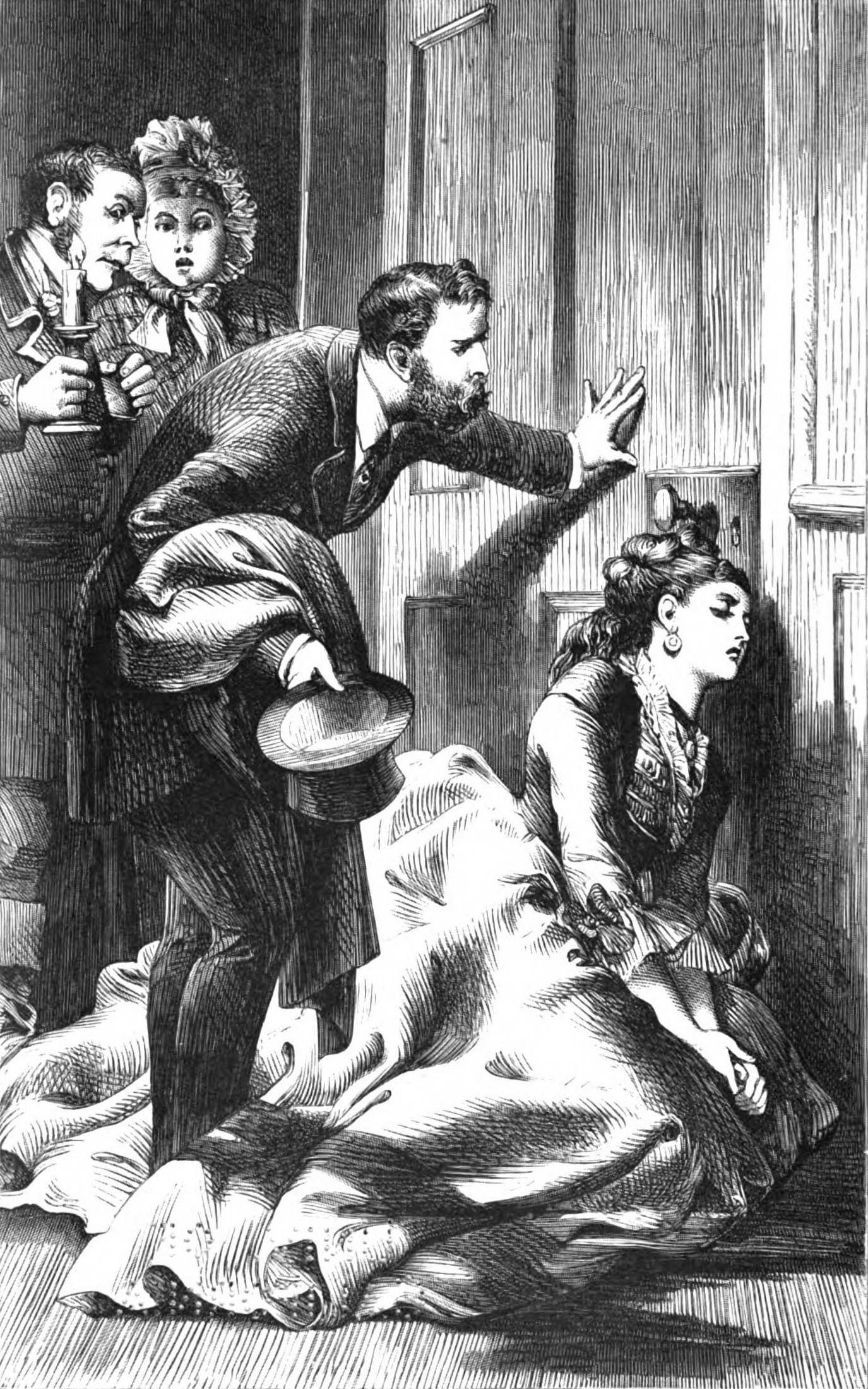

I turned and entered my house. The door closed upon sympathy, life, and light, and I became again the prey of misery and fear. I ran up-stairs, and was astonished to see as I passed that the usually locked door of the front room was standing open. I went in, and found myself in a narrow passage, having a door on either hand; the one on the right was partly open, and it showed me a bedroom in no way different from an ordinary sleeping chamber. At the foot of the bed Mrs. Judson was kneeling down, with her head hidden in her hands. I walked in and put my hand upon her shoulder; she raised her face, swollen with weeping, and said:

"Look round, ma'am. Master has ordered that this room should be opened; and if you desired it, all should be shown to you. This is her bed; in that drawer you will find the dress she wore on the night of her death."

I went to a heavy old-fashioned chest of drawers, and opening the top one, saw a torn yellow lace veil, which I recognised at once, and an old white dress. I looked at them with amazement and sorrow.

"She often put them on," said Mrs. Judson, "and she sat in them talking about her wedding-day; and master never crossed her in her fancies."

"Was she ever married, then?" I asked. Mrs. Judson stared at me for a moment or two, and then said:

"You must ask master everything; things will be different now. He has only told me to let you into these rooms."

"Where did you sleep," I asked, "when Miss Connor was alive?"

"In the room on the other side of the little passage; there is a door out of that leading up to the room where I now sleep."

I looked round and marked a few books, dusty with long disuse, and a few common articles of daily use, a workbox, and old desk without a lock and stained with ink.

"Did she ever write?" I asked.

Mrs. Judson coloured, changed most painfully, as if the question struck on some very sensitive chord of her memory.

"Yes," she said in a hollow voice. "Do you wish to stay any longer, ma'am? I must leave you; the room is too sad for me; I cannot bear it."